Life After Life, review: a Groundhog Day period

drama that makes you care about its characters

Kate Atkinson's 2013 bestseller has been gorgeously

adapted for TV with almost everything intact

4 / 5 stars

By

Anita

Singh,

ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR

19 April

2022 • 10:00pm

It’s BBC

period drama time. Adopt the brace position. What crimes against historical

accuracy are we about to witness? Which 21st-century preoccupations will be

shoehorned into the script? Will Olivia Colman be in it?

With great

relief, I can tell you that none of the above applies to Life After Life. It is

a gorgeously-realised and entirely faithful adaptation of Kate Atkinson’s 2013

bestseller. The fact that it is a modern book, with a female author and

protagonist, means that nobody has felt the need to tinker with the story. It

has been transferred from page to screen with almost everything intact,

including lines from the novel narrated here by Lesley Manville.

Voiceovers

can often be an ominous sign in television, signalling a director who lacks

confidence in their own power of storytelling. But here it works fine. If you

are a fan of the book - and millions are - this drama should be pleasing.

The story

is a fantastical one. Ursula Todd is stillborn on February 11, 1910, the

umbilical cord wrapped around her neck and only a young housemaid by the

mother’s bedside. But then we cut to the same scene, and Ursula lives - this

time a doctor is present.

A few years

later, she drowns while playing at the seaside. Then we spool back, live those

few years again, and this time an artist painting seascapes spots the little

girl in distress and rescues her from the waves. And so it goes on, with Ursula

dying many times but being born again.

Somehow,

she begins to intuit that death is around the corner and takes decisions that

affect her life chances. “The world was a dangerous place but she was not

powerless - quite the opposite,” the narrator informs us, although it does take

Ursula several attempts to survive the Spanish ‘flu.

Essentially,

this is a literary version of Groundhog Day. It spans two world wars, and will

eventually bring Ursula face to face with Hitler in a moment that could change

the course of history. There is a danger of the story - structurally, it can

never be more than a collection of vignettes - appearing lightweight or

gimmicky. But the quality cast prevents this from happening.

In future

episodes, Thomasin McKenzie will take over from the child actors Eliza Riley

and Isla Johnston as Ursula. In episode one, the most striking role is that of

Ursula’s mother, Sylvie, played by Sian Clifford.

So often in

period dramas, mothers are gentle figures - Lady Bridgerton in Netflix’s

blockbuster series is just the latest example, channelling Little Women’s

Marmee. But Clifford brings a welcome spikiness - the producers surely had her

performance as Fleabag’s sister in mind when they cast her. Sylvie is

short-tempered, undemonstrative, and unable to treat her daughter with

uncomplicated affection. “You’re too old for that,” she tells Ursula, when the

girl tries to curl up on her lap.

The purest

love, in this first episode at least, is between Ursula and her younger

brother, Teddy. It’s curious how affecting these scenes can be when you know

that any tragedy that befalls them is likely to be erased in the next lifetime.

James

McArdle plays Sylvie’s husband, Hugh. His frequent absences are better

explained in the book than they are here, and in the course of this first

episode we were told precious little about him. Yet when he hugged his children

before going off to war, I had a lump in my throat. It is a drama that makes

you care about the lives of its characters, however many times you meet them.

Life After Life review – a thoroughly addictive

weepathon

This adaptation of Kate Atkinson’s novel about a woman

who keeps on dying and being reborn is so full of grief it can feel

overwhelming – but the anguish is irresistible

The show’s main priority is apparent from the start:

to make you cry … Life After Life.

Rachel

Aroesti

Tue 19 Apr

2022 22.00 BST

Ursula Todd

can’t stop dying. That’s the premise of this devastating drama, a four-part

adaptation of Kate Atkinson’s 2013 novel, which documents its protagonist’s

many demises – each as distressing as the last. Born to a wealthy middle-class

family in 1910, Ursula dies almost instantly, strangled by her umbilical cord.

But, then again, she survives – a fact relayed to us by Lesley Manville’s

equanimous narrator. It’s a pattern that repeats throughout Ursula’s many

comfortable childhoods: there’s a drowning incident, a fall out of a bedroom

window, multiple battles with Spanish flu. And then, suddenly, she is back,

being born, and doing it all over again – but this time with self-protective

instincts she can’t quite account for. It’s The Butterfly Effect meets

Groundhog Day (or rather “Groundhog Life”), only with none of the latter’s

droll cosiness.

There’s not

a huge amount to laugh about in Life After Life (BBC Two). The show’s main

priority is apparent from the start: making people cry. If you like the feeling

of being overwhelmed by vicarious trauma and grief then you’re in for a treat.

And the anguish is thoroughly addictive. It’s what makes Life After Life

incredibly compelling, binge-worthy even, despite being practically plotless

from one episode to the next.

The tragedy

of Ursula’s life is amorphous and inevitable and not particularly personal; it

has no through-line besides the fact that the story is set during a uniquely

dangerous time in British history. That’s no accident: it’s what makes her

incessant dying entirely plausible. Although the first world war doesn’t

directly affect her bucolic childhood, it still kills her (her father

volunteers to fight, which then leads to the window fall). The 1918 influenza

pandemic is harrowing – unbelievably so, from the Todds’ perspective,

especially given the timing. “Hasn’t there been enough suffering?” is the

dismissive response of Ursula’s steely, capable mother, unconvinced that there

is a threat until it’s far too late.

Yet it’s

when the action moves into the second world war that the universe darkens more

profoundly. Until this point, Ursula’s lives have got longer and generally

better. Now that progress stalls: she cannot avoid news of her beloved little

brother Teddy’s death, however many times her life reboots. Her wartime

experiences vary wildly – from a glittering civil service career to family life

in Germany that descends into hellish starvation – but they are all deeply

disturbing, the latter almost nauseatingly so.

In one

sense, Life After Life has found a dramatic cheat code. Killing off a

protagonist – especially such a sweet, thoughtful, young one – is a shortcut to

brutal emotional impact. Surely a drama almost entirely made up of that moment,

or the promise of it happening imminently, is an easy way to get viewers on

tenterhooks? And yet it soon begins to feel miraculous that we are never inured

to the awfulness of Ursula’s deaths. You can’t mourn her when you know you’ll

be seeing her in the next scene, and yet you still do.

That’s not

so much because of a particular affection for Ursula (Thomasin McKenzie)

herself. She’s not a hugely distinctive personality, something necessary to

accommodate all the twists her life takes. It’s not even really because of the

convincing nature of the show’s world, though it does a brilliant job of making

period archetypes – the grumpy servant, imperious mother, gadabout maiden aunt

– seem three-dimensional (thanks mainly to the stellar cast: Jessica Hynes,

Fleabag’s Sian Clifford and Jessica Brown Findlay, respectively). What makes

Life After Life so upsetting is that it feels real in a broader way. Whether

these deaths have actually befallen the fictional Ursula is beside the point.

Their historical grounding means we know they happened to somebody, somewhere,

at some time.

Keep

watching Life After Life to make sense of its central mystery – or, indeed, its

central protagonist – and you will be disappointed. Ursula never gets close to

unravelling a purpose behind her predicament. “I don’t know why we live – all

we do is die,” she mourns on a blitz deathbed of rubble and dust towards the

end of the series, still completely mystified by the meaning of her multiple

lives.

Usually,

such drama pulls strings in order to wrap things up with a cheap,

life-affirming glow, but Ursula gets only glimmers of comfort from others. Her

journalist aunt Izzie – a 1920s Carrie Bradshaw – advocates viewing life as an

adventure. Her avuncular psychiatrist quotes Nietzsche on amor fati – embracing

your own fate. Her father, meanwhile, offers more banal words about human

kindness.

Really, it

is less about the content of their advice than the love implicit in it, which

is a powerful consolation for death. That love radiates from Ursula after the

conversation with her father as she boards the train back to wartime London

with a heartbreaking spring in her step, ready to die all over again.

Life After Life by Kate Atkinson – review

Themes of fate, family life and renewal are

brilliantly explored in this story of a life lived in wartime Britain

Alex Clark

Wed 6 Mar

2013 10.54 GMT

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/mar/06/life-after-life-kate-atkinson-review

Kate

Atkinson's new novel is a marvel, a great big confidence trick – but one that

invites the reader to take part in the deception. In fact, it is impossible to

ignore it. Every time you attempt to lose yourself in the story of Ursula Todd,

a child born in affluent and comparatively happy circumstances on 11 February

1910, it simply stops. If this sounds like the quick route to a short book,

don't worry: the narrative starts again – and again and again – but each time

it takes a different course, its details sometimes radically, sometimes

marginally altered, its outcome utterly unpredictable. Atkinson's general rule

is that things seem to get better with repetition, but this, her

self-undermining novel seems to warn us, is a comfort that is by no means

guaranteed, either.

She begins

as she means to go on, and at the very beginning. (In fact, even this is not

quite true: a brief prologue shows us Ursula in a Munich coffee shop in 1930,

assassinating Hitler with her father's old service revolver.) At the start of

the novel "proper", Sylvie Todd is giving birth to her third child,

her situation given a fairytale atmosphere by the encroaching snow which also,

alas, cuts her off from outside help in the form of Dr Fellowes or Mrs Haddock,

the midwife. Ursula is stillborn, with the umbilical cord wrapped around her

neck, her life unsaved for want of a pair of surgical scissors. Fortunately,

though, she is allowed another go at the business of coming into being; in take

two, Dr Fellowes makes it, cuts the cord and proceeds to his reward of a cold

collation and some homemade piccalilli (it might be too fanciful to notice that

even the piccalilli repeats).

Ursula's

childhood is to be punctuated with such near-misses: the treacherous undertow

of the Cornish sea, icy tiles during a rooftop escapade, the wildfire spread of

Spanish flu. Each disaster is confirmed by variations on the phrase

"darkness fell", and each new beginning heralded by the tabula rasa

that snow brings. Ursula carries within her a vague, dimly apprehended sense of

other, semi-lived lives, inexpressible except as impetuous actions – such as

when she pushes a housemaid down the stairs to save her from a more terrible

ending. That misdemeanour lands her in the office of a psychiatrist who

introduces her, in kindly fashion, to the concept of reincarnation and to the

roughly opposing theory of amor fati, particularly as espoused by Nietzsche: the

acceptance, or even embrace, of one's fate, and the rejection of the idea that

anything could, or should, have unfolded differently.

Amor fati

is tough to take, of course, if you are a drowning child, or a battered wife,

or a shell-shocked young man, or a terrified mother calling for your baby in

the rubble of the blitz, all of whom and more besides make up the lives

captured, however fleetingly, in Life After Life. It's equally tough if you are

a novelist, and put in the powerful but invidious position of controlling what

befalls your characters. Are their futures really written in their past? Can

you tell what's going to happen to them simply from the way you started them

off? Even sustaining your creative engagement could prove tricky: perhaps that's

why one catastrophe is tagged with the exhausted words "Darkness, and so

on" and why yet another recitation of Ursula's birth is reduced to a mere

five lines.

The reader

is similarly implicated in this continual manipulation of narrative tension and

the suspension of disbelief. We want a story, but what kind of story do we

want: something truthful or something soothing, something that ties up loose

ends or something that casts us on to a tide of uncertainty, not only about

what might happen, but about what already has? In Atkinson's model, we can have

all of the above, but where does that leave us, with multiple tall tales

clamouring for our attention?

Sometimes,

it appears we are being offered a straight choice between happy and unhappy

endings. On the one hand, there is Fox Corner, the Todd family home in what is

still, although perhaps not for long, a wonderfully bucolic England. There are

gin slings and tennis on the lawn and bees buzzing their "summer afternoon

lullaby"; there is the reliable accumulation of children – Ursula is the

third of five – and servants that are either touchingly steadfast or humorously

difficult; there are beloved family dogs and treasured dolls and troublesome

aunts whose bad behaviour can just about be absorbed.

Outside in

the lane, however, lurks an evil-minded stranger, his story the more powerful

for never being brought into the light; and sometimes intruders arrive under

the cloak of friendship. When Ursula is molested, and then raped, by a pal of

one of her brothers, her exile from Fox Corner begins; her subsequent pregnancy

and illegal abortion give way to a lonely London life, solitary drinking and

then, most awfully, to a violent husband who shuts her up in a mean little

house in Wealdstone, far from her family.

Ursula's

marriage to the vile Derek Oliphant – himself a constructor of false personal

history – would never have happened if she had managed to evade her teenage

abuser. In the next iteration, she does; and she is liberated once more, to

plunge on to lives made perhaps even more divergent by the schism of the second

world war. And the reader is perplexed once more: what to make of a character

so chameleon-like that we can watch her excavating bomb sites on one page,

stranded in a dystopian, war-torn Berlin on another and (in what admittedly

requires the biggest leap of faith) being entertained by the Führer at

Berchtesgaden on yet another?

This

description of Atkinson's looping, metamorphosing narrative inevitably makes it

sound tricksy, almost whimsical. Structurally, it is, but its ceaseless

renewals are populated with pleasures that extend beyond the what-next variety.

She captures well, for example, the traumatic shifts in British society – and

does so precisely because she cuts directly from one war to the next, only

later going back to fill in, partially, what happened in between. She

demonstrates an extraordinary gift for capturing peril: the sections in which

influenza tears through Fox Corner are truly menacing, and the descriptions of

Ursula's work in a bombed-out London are masterpieces of the macabre ("'Be

careful here, Mr Emslie,' she said over her shoulder, 'there's a baby, try to

avoid it.'").

The texture

of daily life is beautifully conveyed, particularly in its domestic details,

which often verge on the queasily visceral. An ineptly poached egg is "a

sickly jellyfish deposited on toast to die"; shortly after Sylvie's

confinement, Mrs Glover, the crosspatch cook, "took a bowl of kidneys

soaking in milk from the pantry and commenced removing the fatty white

membrane, like a caul". On another occasion, she thumps slices of veal

with a tenderiser, imagining "they're the heads of the Boche". But

alongside these minutiae is set the author's fascination with the intricacies of

large families, and in particular with sibling relationships.

The

so-called family saga is, of course, where Atkinson's career as a novelist

began, with the Whitbread-winning Behind the Scenes at the Museum, itself a

story that refused to proceed in linear fashion, invoking the spirit of

Tristram Shandy in its digressive portrayal of the life of Ruby Lennox. Neither

book, of course, can really be contained by such a constricting label, just as

Atkinson's four Jackson Brodie novels refuse to fit neatly into the genre

marked crime. Behind the Scenes and Life After Life both co-opt the family –

its evolution over time, its exponentially multiplying characters and

storylines, its silences and gaps in communication – and use it to show how

fiction works and what it might mean to us. But what makes Atkinson an

exceptional writer – and this is her most ambitious and most gripping work to

date – is that she does so with an emotional delicacy and understanding that

transcend experiment or playfulness. Life After Life gives us a heroine whose

fictional underpinning is permanently exposed, whose artificial status is never

in doubt; and yet one who feels painfully, horribly real to us. How do you

square that circle? You'd have to ask Kate Atkinson, but I doubt she would give

you a straight answer.

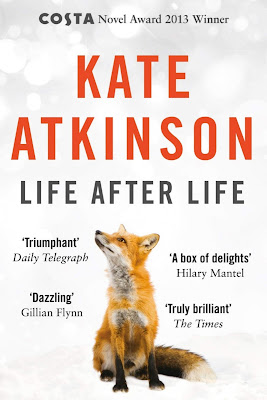

Life After Life is a 2013 novel by Kate Atkinson. It is the first of two novels

about the Todd family. The second, A God in Ruins, was published in 2015. Life

After Life garnered acclaim from critics.

The novel

has an unusual structure, repeatedly looping back in time to describe

alternative possible lives for its central character, Ursula Todd, who is born

on 11 February 1910 to an upper-middle-class family near Chalfont St Peter in

Buckinghamshire. In the first version, she is strangled by her umbilical cord

and stillborn. In later iterations of her life she dies as a child - drowning

in the sea, or when saved from that, by falling to her death from the roof when

trying to retrieve a fallen doll. Then there are several sequences when she

falls victim to the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 - which repeats itself again

and again, though she already has a foreknowledge of it, and only her fourth

attempt to avert catching the flu succeeds.

Then there

is an unhappy life where she is traumatised by being raped, getting pregnant

and undergoing an illegal abortion, and finally becoming trapped in a highly

oppressive marriage, and being killed by her abusive husband when trying to

escape. In later lives she averts all this by being pre-emptively aggressive to

the would-be rapist. In between, she also uses her half-memory of earlier lives

to avert the young neighbour Nancy being raped and murdered by a child

molester. The saved Nancy would play an important role in Ursula's later

life(s), forming a deep love relationship with Ursula's brother Teddy, and

would become a main character in the sequel, A God in Ruins.

Still later

iterations of Ursula's life take her into World War II, where she works in

London for the War Office and repeatedly witnesses the results of the Blitz,

including a direct hit on a bomb shelter in Argyll Road in November 1940 - with

herself being among the victims in some lives and among the rescuers in others.

There is also a life in which she marries a German in 1934, is unable to return

to England and experiences the war in Berlin under the allied bombings.

Ursula

eventually comes to realise, through a particularly strong sense of deja vu,

that she has lived before, and decides to try to prevent the war by killing

Adolf Hitler in late 1930. Memory of her earlier lives also provides the means

of doing that: the knowledge that by befriending Eva Braun - in 1930 an obscure

shop girl in Munich - Ursula would be able to get close to Hitler with a loaded

gun in her bag; the inevitable price, however, is to be herself shot dead by

Hitler's Nazi followers immediately after killing him.

What is

left unclear - since each of the time sequences end with "darkness"

and Ursula's death and does not show what followed - is whether in fact all

these lives actually occurred in an objective world, or were only subjectively

experienced by her. Specifically it is not clear whether or not her killing

Hitler in 1930 actually produced an altered timeline where the Nazis did not

take power in Germany, or possibly took power under a different leader with a

different course of the Second World War. Although in her 1967 incarnation

Ursula speculates with her nephew on this "might have been", the book

avoids giving a clear answer.

Critical

reaction

Alex Clark

of The Guardian gave Life After Life a positive review, saying that domestic

details of daily life are conveyed beautifully, and that traumatic shifts in

British society are also captured well "precisely because she cuts

directly from one war to the next, only later going back to fill in, partially,

what happened in between." Clark argued that the novel "[co-opts] the

family [...] and [uses] it to show how fiction works and what it might mean to

us [...] with an emotional delicacy and understanding that transcend experiment

or playfulness. Life After Life gives us a heroine whose fictional underpinning

is permanently exposed, whose artificial status is never in doubt; and yet one

who feels painfully, horribly real to us." The Daily Telegraph's Helen

Brown likewise praised it, calling it Atkinson's best book to date.[3] The

Independent found the central character to be sympathetic, and argued that the

book's central message was that World War II was preventable and should not

have been allowed to happen.

Janet

Maslin of The New York Times Book Review praised Life After Life as Atkinson's

"very best" book and "full of mind games, but they are

purposeful rather than emptily playful. [...] this one connects its loose ends

with facile but welcome clarity." She described it as having an

"engaging cast of characters" and called the depiction of the British

experience of World War II "gutsy and deeply disturbing, just as the

author intends it to be."[4] Francine Prose of The New York Times wrote

that Atkinson "nimbly succeeds in keeping the novel from becoming

confusing" and argued that the work "makes the reader acutely

conscious of an author’s power: how much the novelist can do."

The Wall

Street Journal's Sam Sacks dubbed Life After Life a "formidable bid"

for the Man Booker Prize (though the novel was ultimately not longlisted). He

said the high-concept premise of "Ursula [contriving] to avoid the

accident that previously killed her [...] blends uneasily with what is

otherwise a deft and convincing portrayal of an English family's evolution

across two world wars [...] all the other characters seem complexly armed with

free will." He found the resolution related to the prologue as

"rushed and anti-climactic". But Sacks also said that "she

[brings] characters to life with enviable ease", referring to the erosion

of Sylvie and Hugh's marriage as "poignantly charted". Also, like

Maslin, he lauded the novella-length Blitz chapter as "gorgeous and

nerve-racking".

In NPR,

novelist Meg Wolitzer suggested that the book proves that "a

fully-realised world" is more important to the success of a fiction work

than the progression of its story, and dubbed it a "major, serious yet

playfully experimental novel". She argued that by not choosing one path

for Ursula, Atkinson "opened her novel outward, letting it breathe

unrestricted".

The

Guardian's Sam Jordison expressed mixed feelings. He commended the depiction of

Ursula and her family, and Atkinson's "fine storytelling and sharp eye for

domestic detail". He argued, "There is real playfulness in these

revisited moments and repetition never breeds dullness. Instead, we try to spot

the differences and look for refractions of the same scene, considering the

permutations of what is said and done. It can provide an enjoyable and

interactive experience." He criticised the portions outside Britain,

however, and said overall that the book has "an abundance of human warmth,

but it just isn't convincing. There is much to enjoy – but not quite enough to

admire."

In 2019,

Life After Life was ranked by The Guardian as the 20th best book since 2000. It

was written that the "dizzying fictional construction is grounded by such

emotional intelligence that her heroine’s struggles always feel painfully,

joyously real." The novel was 20th in Paste's list of the 40 best novels

of the 2010s, with Alexis Gunderson arguing, "No one gets to live as many

lives and have as many second chances to get the next step right as protagonist

Ursula Todd. But in a decade where the real world swung between wars and

elections, there are few more clarifying literary escapes than Life After Life.

[...] Atkinson’s sage weaves a heartbreaking, frightening and beautiful journey

that’s written with tenacity and grace."

It was

listed as one of the decade's top 10 fiction works by Time, where it was billed

as "a defining account of wartime London, as Ursula experiences the

devastation of the Blitz from various perspectives, highlighting the senselessness

of bombing raids. The story of her multiple lives is both moving and

lighthearted, filled with comic asides and evocative language about life’s many

joys and sorrows." Entertainment Weekly ranked it second, with David

Canfield arguing that Life After Life "seamlessly executes an

idiosyncratic premise [...] and contains a seemingly endless capacity to

surprise", but that it "will stand the test of time for its

in-between moments — its portraits of wartime, its glimpses into small domestic

worlds, its understanding of one woman’s life as filled with infinite

possibilities." The novel was among the honourable mentions on the

Literary Hub list of the 20 best novels of the decade.

_cover_image.jpg)

.jpeg)