The Lloyd Family

https://www.greatdixter.co.uk/the-lloyd-family

Nathaniel

and Daisy Lloyd brought up six children at Great Dixter where they all

developed a lasting attachment to the house and a deep knowledge of the garden.

One of the bathrooms still has the pencil marks on a wall recording their

increasing height year by year. Selwyn (1909-35), the eldest child, went into

the family business but died at a young age from TB; Oliver (1911-85), whose

second Christian name Cromwell spoke of Daisy’s ancestral connections, became a

medical doctor and academic; Patrick (1913-56) was a professional soldier and

died on active service in the Middle East; Quentin (1916-95) served as the

estate manager for Great Dixter for many years; Letitia (1919-74) trained as a

nurse; Christopher (1921-2006), the youngest child, was born in the north

bedroom of the Lutyens wing and for the rest of his life Dixter was his home.

The

Lloyd children photographed in height order at Great Dixter

Daisy

Lloyd and Christopher Lloyd in the meadow at Great DixterWith the renovations

and extension complete by 1912, Great Dixter was a large and comfortable family

home. Central heating and electric lighting were installed from the outset and

there was a domestic staff of five or more, including a chauffeur, a cook, two

housemaids and a nursery maid. Outside staff included nine gardeners. For four

years during the First World War, part of the house became a hospital and a

total of 380 wounded soldiers passed through the temporary wards created in the

great hall and the solar. In the Second War, Dixter housed 10 evacuee boys from

September 1939 until it was decided that they should go further west and away

from the path of enemy aircraft.

After

Nathaniel’s death in 1933, the formidable Daisy was in control until her own

demise in 1972. Her contribution to the garden was most evident in the wild

flower meadows but her passion for all things plant related was as extensive as

it was infectious.Daisy Lloyd wearing Austrian peasant costume on the steps of

the Yeomans hall

She was

a determinedly energetic lady, an accomplished cook and brilliant embroiderer,

who, having taken to wearing Austrian peasant costume, cut an eccentric figure

on the local scene.

Nathaniel Lloyd OBE FSA (5 March 1867 – 8 December 1933) was a

business man who, later in life, studied architecture as a pupil of Sir Edwin

Lutyens and became an architectural historian and author. He owned the Grade 1

listed house Great Dixter in East Sussex, now a legacy left to the nation by

his youngest child, Christopher Lloyd, the gardener and author.

Born in

Oswaldtwistle, Lancashire to John and Rachel Lloyd, a comfortably well off

middle class family, Nathaniel Lloyd started his career with the Mazawattee Tea

Co and was responsible for its advertising and printing at the height of its

expansion. In 1893, Lloyd left the tea company and founded his own business,

Nathaniel Lloyd & Co, Lithographic Printers. This successful colour

printing firm was responsible for numerous advertising posters, for example, a

poster for ‘Lazenby’s “Chef” Sauce and other delicacies’ held in the

collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum and posters printed to aid the

war effort held by the Science Museum, London. It was so successful that Lloyd

was able to take partial early retirement in 1909, becoming joint managing

director of the Star Bleaching Co, which he sold in 1912 and turned to his

second career in architecture.

Lloyd

studied architectural drawing and set up a small practice. He was appointed a

Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1931[10] and was also a

Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London and a member of the London

Survey Committee. Lloyd was a keen photographer who took many of the

photographs for his books and his collection, of over 3600 prints and

negatives, mostly taken between 1910 and 1930, was acquired by Historic England

in 1997.Photographs by Nathaniel Lloyd are also held by the National Trust and

in the Conway Library, whose archive of mainly architectural images is being

digitised under the wider Courtauld Connects project.

Great

Dixter

When he

retired from his business in 1909, Nathaniel Lloyd began looking for an old

house to buy and renovate. In 1910 he purchased the 15th century manor house

Dixter for the sum of £6,000 and also bought a 16th century timbered yeoman’s

house in Benenden Kent, subject to a demolition order, for £75, dismantling it

and moving it to Dixter. He commissioned Edwin Lutyens and together they

renovated the houses, built onto them and designed the 5 acre garden. At that

time it was renamed Great Dixter.

Lloyd was

always conscious that the work should be conducted sympathetically and true to

its period and, after the restoration was completed in 1912, he wrote in a

memorandum of 1913; "The spirit in which the work has been done may be

summed up by saying that nothing has been done without authority, nothing has

been done from imagination; there has been no forgery". 1913 was also the

year in which Great Dixter first appeared in the magazine Country Life in an

illustrated article.

Both

Nathaniel and his wife, Daisy took an interest in the extensive gardens at

Great Dixter, employing nine gardeners, and that interest was continued by

their youngest son Christopher Lloyd. After taking a degree in horticulture at

Wye College in Kent and becoming an associate lecturer at the college for four

years, Christopher returned to Great Dixter in 1954 and set up a plant nursery.

From 1963 onwards he wrote the weekly column ‘In My Garden’ which appeared in

Country Life for over 40 years. Christopher continued to live in Great Dixter

and regularly opened the house and gardens to the public. Prior to his death he

set up The Great Dixter Charitable Trust to run the estate and continue to open

the house and garden to visitors.

Private

life

In 1905

Nathaniel Lloyd married Daisy Field[3] and they had six children, 5 sons,

Selwyn (1909–35), Oliver (1911–85), Patrick (1913–56), Quentin (1916–95),

Christopher (1921-2006) and 1 daughter, Letitia (1919–74). After Nathaniel’s

death in 1933, Daisy Lloyd took over the running of the estate, assisted by

Christopher, until her death in 1972, aged 91.

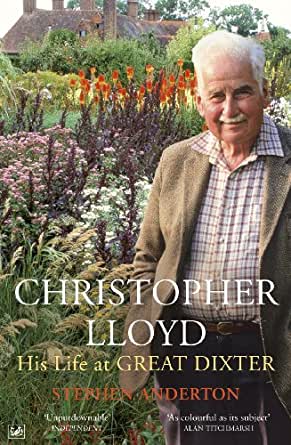

Christopher "Christo" Hamilton Lloyd, OBE (2 March 1921 – 27 January

2006) was an English gardener and a gardening author of note, as the

20th-century chronicler for thickly planted, labour-intensive country

gardening.

Lloyd was

born in Great Dixter, into an upper-middle-class family, the youngest of six

children. In 1910, his father, Nathaniel Lloyd, an Arts and Crafts architect,

author, printer and designer of posters and other images for confectionery

firms, bought Great Dixter, a manor house in Northiam, East Sussex near the

south coast of England. Edwin Lutyens was hired to renovate and extend the

house and advise on the structure of the garden. Nathaniel Lloyd loved gardens,

designed some of this one himself, and passed that love on to his son. Lloyd

learned the skills required of a gardener from his mother Daisy, who did the

actual gardening and introduced him as a young boy to Gertrude Jekyll,[3] who

was a considerable influence on Lloyd, in particular with respect to

"mixed borders". His mother Daisy, to whom he had remained close his

entire life, died at Great Dixter on 9th June 1972, aged 91.

After

Wellesley House (Broadstairs) and Rugby School, he attended King's College,

Cambridge, where he read modern languages before entering the Army during World

War II.[7] After the war he received his bachelors in Horticulture from Wye

College, University of London, in 1950. He stayed on there as an assistant

lecturer in horticulture[8] until 1954.

In 1954,

Lloyd moved home to Great Dixter and set up a nursery specialising in unusual

plants. He regularly opened the house and gardens to the public.[9] Lloyd did

not do all of the gardening himself, but, like his parents, employed a staff of

gardeners. In 1991, Fergus Garrett became his head gardener, and continued in

that role after Lloyd's death.

In 1979

Lloyd received the Victoria Medal of Honour, the highest award of the Royal

Horticultural Society, for his promotion of gardening and his extensive work on

their Floral Committee.[10] In 1996, Lloyd was awarded an honorary doctorate

from the Open University. In 2000, he was appointed as an officer of the Order

of the British Empire.

Lloyd was a

great-grandson of Edwin Wilkins Field, a law-reforming solicitor, and the great

uncle of Christopher Lloyd, the author of numerous non-fiction books, including

the popular What on Earth? Happened from the Big Bang to the Present Day and a

series of children's historical Wallbook titles.

Christopher

Lloyd

Doyen of gardening writers famed for his innovative

planting at Great Dixter

Rosemary

Alexander

Mon 30 Jan

2006 11.19 GMT

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2006/jan/30/pressandpublishing.booksobituaries

The

gardener and writer Christopher Lloyd, who has died aged 84 following a stroke,

was the supreme master of his profession. Awarded in 1979 the Victoria Medal of

Honour, the highest horticultural accolade, he was the best informed, liveliest

and most innovative gardening writer of our times.

The author

of a string of classic books and, until last October, 42 years' worth of

regular weekly articles in Country Life, he was, until his death, gardening

correspondent of the Guardian. His garden at Great Dixter, in east Sussex, gave

pleasure to thousands of visitors and provided a springboard for conveying

ideas - successes and disappointments - to his readers in a relaxed and

non-technical manner.

One of six

children, Lloyd was born at Great Dixter, into a strictly run household, where

no smoking or drinking was permitted. His father, Nathaniel Lloyd, came from a

comfortably off middle-class family in Manchester and his mother, Daisy Field,

was reputedly a descendant of Oliver Cromwell. Nathaniel had bought Great

Dixter in 1910, and commissioned Edwin Lutyens to restore and add to its

15th-century buildings. Lutyens also set out the framework of the garden as an

array of formal spaces, which still exist today. Nathaniel died in 1933,

leaving the 450-acre estate to his formidable widow.

Lloyd was

educated at Wellesley House, Rugby and King's College, Cambridge, where he took

an MA in modern languages. Having inherited his mother's passion for flowers,

he studied horticulture at Wye College - in those days it was a general degree,

including science and botany - and was an assistant lecturer there from 1950 to

1954.

Returning

to the family home that year, he started a nursery, specialising in clematis

and uncommon plants (Vita Sackville West gave him cuttings of the original

rosemary from Corsica, r.beneden blue). Sharing their enthusiasm for gardening,

mother and son continued to develop the gardens and encourage visitors until

Daisy died in 1972. The house and garden then became the property of

Christopher and his niece Olivia.

In 1957, after

experimenting with Dixter's long border, Christopher wrote his first book, The

Mixed Border, propounding the then revolutionary idea of combining shrubbery

and herbaceous border. In 1965 came two further books, now modern classics:

Clematis (with John Treasure), and Trees and Shrubs for Small Gardens, both of

which combined technical knowledge with a humorous and informed sense of

English style. In May 1963, he was persuaded by Arthur Hellyer to start his

Country Life column. He always thought of something new to say, producing copy

on time, even, on one occasion, from his hospital bed.

As a result

of Christopher's writing, Great Dixter is the most documented of gardens, its

most celebrated feature being the immense mixed border, measuring 210ft x 15ft,

planned for midsummer, but in reality extending from April to October. More

recently, bored by his celebrated but diseased rose garden, he announced that

roses were "miserable and unsatisfactory shrubs". Encouraged by his

protege and head gardener Fergus Garrett - but to the alarm of the gardening

cognoscenti - he created a tropical garden, proving that dahlias, the Japanese

banana (musa basjoo), cannas and caster oil plants can extend the colourful

gardening season through to the first frosts, provided they are well wrapped in

winter.

Occasionally

referred to as the "ill tempered gardener", a play on the title of

his 1970 book The Well Tempered Garden, Christopher did not suffer fools

gladly, occasionally refusing to divulge the name of a plant to non-serious

visitors without notebooks. Far from being a plant snob, however, he used both

the essential Latin and the common names of plants, and was always generous in

sharing his knowledge and hospitality.

Life at

Great Dixter was conducted as an ongoing house party. Once, after Christopher's

dachshunds (with whom he shared the house) ate the sandwiches of a group of

Hungarian students, he invited them to be his house guests. He enjoyed

encouraging young people with an interest in gardens and always remained loyal

to his students at Wye College.

He also

wrote about his enjoyment of cooking, and eating homegrown fruit and

vegetables. Fervent about food - inspired by his mother, by Jane Grigson and,

more recently, by Delia Smith - he was an expert classic cook. He served

straight from the stove and hated books with "glamorously laid out meals

and violently coloured illustration". He was averse to mechanisation,

though he doted on the Magimix given to him by his friend Beth Chatto, with

whom he wrote Dear Friend and Gardener (1998). An enthusiastic traveller,

journeying regularly to the United States or Australia on lecture tours, he

cherished his annual holiday in the Hebrides, where he could indulge in walking

and whisky.

An

irrepressible socialiser, Christopher was an inspiration to all and a mentor to

many distinguished horticulturalists and garden writers. When staying with

Marco Polo Stufano, then director of Wave Hill botanic garden in New York, who

had every book by Christopher in his library, he not only signed each one but

wrote a different note in each. A master of the non-sequitur, when asked on the

telephone if a visit to Great Dixter could be arranged he would ask

"Why?".

His 80th

birthday was celebrated by an ongoing 24-hour event - lunch, a recital by

Graham Gough, dinner and breakfast - that brought together friends from all

over the world. To the end, Christopher and Fergus, who had brought new energy

and enthusiasm into Christopher's life, conspired to enliven the planting. In

later years, Christopher added television to his media, his audacious wit and

puckish comments enlivening each programme.

Christopher

Lloyd challenged people's thinking through his writing and his friendship. His

innovative influence on gardens and garden journalism, and his beloved garden

itself, will remain a legacy for our future.

Polly

Pattullo writes: Not long ago, on a visit to Great Dixter, I noticed a figure

in the famous long border, on his knees, trug by his side, like Beatrix

Potter's Mr McGregor among the cucumber frames. It was Christopher who got to

his feet, wiped his hands on his trousers and beamed. He enjoyed wandering

around Dixter unrecognised - in old jumpers and corduroys - eavesdropping on

the comments of the public.

He was

prepared to utter gardening heresies; indeed, he enjoyed communicating his

radical views. On a March visit, he pointed out a startling display of pale

blue and baby pink hyacinths under a bush of orange-stemmed spiraea; he

chuckled and told us that his old friend Beth Chatto had commented that this

colour scheme "jarred". But Christopher's aim was not to shock - he

wanted to stimulate the sometimes precious world of gardening.

He was a

man of great erudition; besides gardens and food, he knew a lot about opera -

he regularly went to Glyndebourne, whose gardens he found somewhat wanting. He

was also modest: he wrote in his preface to The Adventurous Gardener (1983):

"Never take the 'I shan't see it' attitude. By exercising a little vision

you will come to realise that the tree, which has a possible future, perhaps a

great one, may be more important than yourself, nearing your end."

Always

planning ahead, delighting in experiment, he passionately wanted everyone to

join him on the gardening journey which he had cherished for so long.

·

Christopher Lloyd, gardener and writer, born March 2 1921; died January 27 2006

No comments:

Post a Comment