David Levine, Biting Caricaturist, Dies at 83

By Bruce

Weber

Dec. 29,

2009

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/30/arts/design/30levine.html

David

Levine, whose macro-headed, somberly expressive, astringently probing and

hardly ever flattering caricatures of intellectuals and athletes, politicians

and potentates were the visual trademark of The New York Review of Books for

nearly half a century, died Tuesday in Manhattan. He was 83 and lived in

Brooklyn.

His death,

at New York Presbyterian Hospital, was caused by prostate cancer and a

subsequent combination of illnesses, his wife, Kathy Hayes, said.

Mr.

Levine’s drawings never seemed whimsical, like those of Al Hirschfeld. They

didn’t celebrate neurotic self-consciousness, like Jules Feiffer’s. He wasn’t

attracted to the macabre, the way Edward Gorey was. His work didn’t possess the

arch social consciousness of Edward Sorel’s. Nor was he interested, as Roz

Chast is, in the humorous absurdity of quotidian modern life. But in both style

and mood, Mr. Levine was as distinct an artist and commentator as any of his

well-known contemporaries. His work was not only witty but serious, not only

biting but deeply informed, and artful in a painterly sense as well as a

literate one; he was, in fact, beyond his pen and ink drawings, an accomplished

painter. Those qualities led many to suggest that he was the heir of the

19th-century masters of the illustration, Honoré Daumier and Thomas Nast.

Especially

in his political work, his portraits betrayed the mind of an artist concerned,

worriedly concerned, about the world in which he lived. Among his most famous

images were those of President Lyndon B. Johnson pulling up his shirt to reveal

that the scar from his gallbladder operation was in the precise shape of the

boundaries of Vietnam, and of Henry Kissinger having sex on the couch with a

female body whose head was in the shape of a globe, depicting, Mr. Levine

explained later, what Mr. Kissinger had done to the world. He drew Richard M.

Nixon, his favorite subject, 66 times, depicting him as the Godfather, as

Captain Queeg, as a fetus.

With those

images and others — Yasir Arafat and Ariel Sharon in a

David-and-Goliath parable; or Alan Greenspan, with scales of justice, balancing

people and dollar bills, hanging from his downturned lips; or Chief Justice

John G. Roberts Jr. carrying a gavel the size of a sledgehammer — Mr. Levine’s drawings sent out angry distress signals that

the world was too much a puppet in the hands of too few puppeteers. “I would

say that political satire saved the nation from going to hell,” he said in an

interview in 2008, during an exhibit of his work called “American Presidents”

at the New York Public Library.

Even when

he wasn’t out to make a political point, however, his portraits — often

densely inked, heavy in shadows cast by outsize noses on enormous,

eccentrically shaped heads, and replete with exaggeratedly bad haircuts, 5

o’clock shadows, ill-conceived mustaches and other grooming foibles — tended to

make the famous seem peculiar-looking in order to take them down a peg.

“They were

extraordinary drawings with extraordinary perception,” Jules Feiffer said in a

recent interview about the work of Mr. Levine, who was his friend. He added:

“In the second half of the 20th century he was the most important political

caricaturist. When he began, there was very little political caricature, very

little literary caricature. He revived the art.”

David

Levine was born on Dec. 20, 1926, in Brooklyn, where his father, Harry, ran a

small garment shop and his mother, Lena, a nurse, was a political activist with

Communist sympathies. A so-called red diaper baby, Mr. Levine leaned

politically far to the left throughout his life. His family lived a few blocks

from Ebbetts Field, where young David once shook the hand of President Franklin

D. Roosevelt, who became a hero, as did his wife, Eleanor. Years later, Mr.

Levine’s caricature of Mrs. Roosevelt depicted her as a swan.

“I thought

of her as beautiful,” he said. “Yet she was very homely.”

As a boy he

sketched the stuffed animals in the vitrines at the Brooklyn Museum. He served in

the Army just after World War II, then graduated from Temple University in

Philadelphia with a degree in education and another degree from Temple’s Tyler

School of Art. He also studied painting at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, and

with the Abstract Expressionist painter and renowned teacher Hans Hofmann.

Indeed,

painting was Mr. Levine’s first love; he was a realist, and in 1958 he and

Aaron Shikler (whose portrait of John F. Kennedy hangs in the White House)

founded the Painting Group, a regular salon of amateurs and professionals who,

for half a century, got together for working sessions with a model. A

documentary about the group, “Portraits of a Lady,” focusing on their

simultaneous portraits of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, was made in 2007; the

portraits themselves were exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery.

Mr.

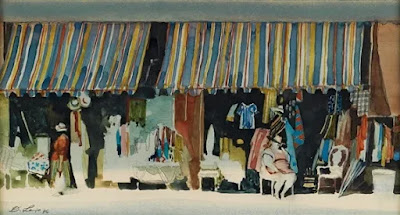

Levine’s paintings, mostly watercolors, take as their subjects garment workers — a tribute to

his father’s employees,

who he said never believed that their lives could be seen as connected to

beauty — or the bathers at his beloved Coney Island. In

a story he liked to tell, he was painting on the boardwalk when he was

approached by a homeless man who demanded to know how much he would charge for

the painting. Mr. Levine, nonplussed, said $50.

“For that?”

the man said.

The

paintings are a sharply surprising contrast to his caricatures: sympathetic

portraits of ordinary citizens, fond and respectful renderings of the

distinctive seaside architecture, panoramas with people on the beach.

“None of

Levine’s hard-edged burlesques prepare you for the sensuous satisfactions of

his paintwork: the matte charm of his oil handling and the virtuoso refinement

of his watercolors,” the critic Maureen Mullarkey wrote in 2004. “Caustic humor

gives way to unexpected gentleness in the paintings.”

Mr.

Levine’s successful career as a caricaturist and illustrator took root in the

early 1960s, when he started working for Esquire. He began contributing cover

portraits and interior illustrations to The New York Review of Books in 1963,

its first year of publication, and within its signature blocky design his

cerebral, brooding faces quickly became identifiable as, well, the cerebral,

brooding face of the publication. He always worked from photographs, reading

the accompanying article first to glean ideas.

“I try

first to make the face believable, to give another dimension to a flat, linear

drawing; then my distortions seem more acceptable,” he said.

From 1963

until 2007, after Mr. Levine received a diagnosis of macular degeneration and

his vision deteriorated enough to affect his drawing, he contributed more than

3,800 drawings to The New York Review. Over the years he did 1,000 or so more

for Esquire; almost 100 for Time, including a number of covers (one of which,

for the 1967 Man of the Year issue, depicted President Johnson as a raging and

despairing King Lear); and dozens over all for The New Yorker, The New York

Times, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone and other publications.

Mr.

Levine’s first marriage ended in divorce. Besides Ms. Hayes, his partner for 32

years whom he married in 1996, he is survived by two children, Matthew, of

Westport, Conn., and Eve, of Manhattan; two stepchildren, Nancy Rommelmann, of

Portland, Ore., and Christopher Rommelmann, of Brooklyn; a grandson, and a

stepgranddaughter.

“I might

want to be critical, but I don’t wish to be destructive,” Mr. Levine once said,

explaining his outlook on both art and life. “Caricature that goes too far

simply lowers the viewer’s response to a person as a human being.”

David Levine (1926-2009): The World He Saw: Five Decades

of Paintings and Drawings

Hamill,

Pete

ISBN:

9780967582610

Issued in

conjunction with a 2014-2015 exhibition of artwork by American artist David

Levine (1926-2009). With an introductory essay by Pete Hamill. Illustrated

artwork falls into these categories: Coney Island, Shmata Queens, Garment

Workers, and Caricatures. Includes chronology, bibliography, and exhibitions

and collections histories. Scarce.

David Levine (December 20, 1926 – December 29, 2009) was an American artist and

illustrator best known for his caricatures in The New York Review of Books.

Jules Feiffer has called him "the greatest caricaturist of the last half

of the 20th Century".

Levine was

born in Brooklyn, where his father Harry ran a small clothing factory. His

mother, Lena, was a nurse and political activist who had communist sympathies.

He began to draw as a child, displaying a precocious talent that, at the age of

nine, won him an invitation to audition for an animator's position in Disney's

Los Angeles Studios.

Levine

later studied painting at Pratt Institute, at Temple University's Tyler School

of Art in Philadelphia in 1946, and with Hans Hofmann. Immediately following

World War II, Levine served in the U. S. Army. After his service, he graduated

from Temple with a degree in education and completed his studies at its Tyler

School.

Career

Levine

initially hoped to be a full-time painter, but was often forced to subsist on

illustration work from publications like Gasoline Retailer. Nevertheless, he

turned out a body of paintings, although many of these were destroyed in a fire

in 1968. Levine's paintings are mostly watercolors that often depict garment

workers, honoring his father's employees, and bathers at Coney Island. The

paintings, in contrast to his illustrations, are "sympathetic portraits of

ordinary citizens, fond and respectful renderings of the distinctive seaside

architecture, panoramas with people on the beach." Levine, together with

Aaron Shikler founded the Painting Group in 1958, a salon of artists with whom

he gathered for fifty years to paint models. The group was the subject of a

2007 documentary called Portraits of a Lady, which followed their creation of

simultaneous portraits of U. S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor.

A job at

Esquire in the early 1960s saw Levine develop his skills as a political

illustrator.[2] His first work for The New York Review of Books appeared in

1963, just a few months after the paper was founded. Subsequently, he drew more

than 3,800 pen-and-ink caricatures of famous writers, artists and politicians

for the publication. Levine would review a draft of the article to be

illustrated, together with photos or other images sent by the staff of the

Review. Within a few days, he would return a finished drawing that caught

"a large fact about his subject's character"; "his brilliance

lay in weaving [the article's] ideas with his own". Only about half of

Levine's caricatures were created for the Review. Other work has appeared in

Esquire (over 1,000 drawings), The New York Times, The Washington Post, Rolling

Stone, Sports Illustrated, New York, Time, Newsweek, The New Yorker, The

Nation, Playboy, and others.

As a

caricaturist for these publications, Levine distinguished his process from that

of political cartoonists: "I could take time to really look it over and

think about it, read the articles and so on. The political cartoonists don't

get a chance. The headlines are saying this and this about so-and-so, and you

have to come up with something which is approved by an editor. I almost never

had to get an approval. In forty years I may have run into a disagreement with

The New York Review maybe two times." However, as his son Matthew Levine

wrote in 1979, on at least three occasions The New York Times refused to print

works it had specifically commissioned David Levine to draw for its op-ed page,

including cartoons of Henry Kissinger, Richard Nixon, and former New York mayor

Ed Koch.

In 1967 he

was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member and became

a full Academician in 1971.

Levine's

work has been exhibited extensively in galleries and museums around the world,

and several collections of his paintings and drawings have been published by

the Review and elsewhere, such as The Arts of David Levine, published by Knoph

in 1978.[8] In 2008, he published a book, American Presidents, featuring his

drawings of U.S. Presidents over five decades,[9] which was also the basis for

an exhibit at the New York Public Library.

Reputation

John

Updike, whom Levine drew many times, wrote in the 1970s: "Besides offering

us the delight of recognition, his drawings comfort us, in an exacerbated and

potentially desperate age, with the sense of a watching presence, an eye

informed by an intelligence that has not panicked, a comic art ready to encapsulate

the latest apparitions of publicity as well as those historical devils who

haunt our unease. Levine is one of America's assets. In a confusing time, he

bears witness. In a shoddy time, he does good work."

The New

York Times described Levine's illustrations as "macro-headed, somberly

expressive, astringently probing and hardly ever flattering caricatures of

intellectuals and athletes, politicians and potentates" that were

"heavy in shadows cast by outsize noses on enormous, eccentrically shaped

heads, and replete with exaggeratedly bad haircuts, 5 o'clock shadows,

ill-conceived mustaches and other grooming foibles ... to make the famous seem

peculiar-looking in order to take them down a peg". The paper commented:

"His work was not only witty but serious, not only biting but deeply

informed, and artful in a painterly sense as well as a literate one."

Levine drew his most frequent subject, former president Richard M. Nixon, 66

times, depicting him as, among other things, the Godfather, Captain Queeg, and

a fetus.

According

to Vanity Fair, "Levine put together a facebook of human history ... the

durability of those Levine depicted, plus the unique insight with which he drew

them, guarantees the immortality of his works". Levine's work, taken as a

whole, had a leftwing bent, and he claimed still to be a communist, although

people of all political persuasions came in for the same acid treatment in

Levine's caricatures. Levine said that "by making the powerful

funny-looking ... he might encourage some humility or self-awareness".

Levine also described his purpose as follows: "Caricature is a form of

hopeful statement: I'm drawing this critical look at what you're doing, and I

hope that you will learn something from what I'm doing."

Last years

and death

In 2006,

Levine was diagnosed with macular degeneration, an eye disease that leads to

blindness. While the Review continued to run Levine's older work, no new work

appeared there after April 2007.

On December

29, 2009, Levine died at New York Presbyterian Hospital at the age of 83. His

death was caused by prostate cancer and a number of subsequent illnesses. He

was survived by his second wife, Kathy Hayes (whom he married in 1996), two

children, Matthew and Eve, two stepchildren, Nancy and Christopher Rommelmann

and grandchildren.

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment