Charlotte Perriand

(24 October 1903 – 27 October 1999) was a French architect and

designer. Her work aimed to create functional living spaces in the

belief that better design helps in creating a better society. In her

article "L’Art de Vivre" from 1981 she states "The

extension of the art of dwelling is the art of living—living in

harmony with man’s deepest drives and with his adopted or

fabricated environment."

Perriand was born in

Paris, France to a tailor and a seamstress. In 1920, she enrolled in

the Ecole de L'Union Centrale de Arts Decoratifs ("School of the

Central Union of Decorative Arts") to study furniture design

from 1920 until 1925. One of her noted teachers during this period

was Art Deco interior designer Henri Rapin.

After applying to

work at Le Corbusier's studio in 1927 and being famously rejected

with the reply "We don’t embroider cushions here",

Perriand renovated her apartment into a room with a large bar made of

aluminum glass and chrome. She recreated this for the Salon

d’Automne, gaining notice from Le Corbusier's partner, Pierre

Jeanneret, convincing Corbusier to offer her a job in furniture

design. There, she was in charge of their interiors work and

promoting their designs through a series of exhibitions.

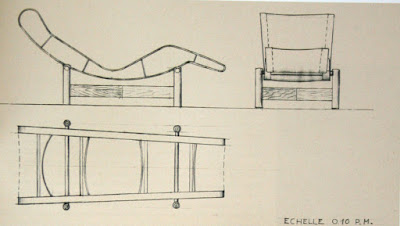

In 1928 she designed

three chairs from Corbusier's principles. Each chair had a

chromium-plated tubular steel base. At Corbuiser's request a chair

was made for conversation: the B301 sling back chair, another for

relaxation: the LC2 Grand Comfort chair, and the last for sleeping:

the B306 chaise longue.

Perriand was

familiar with Thonet's bentwood chairs and used them often not only

for inspiration but also in her designs. Their chaise longue, for

this reason, bears some similarity to Thonet's bentwood rocker

although it doesn't rock. The chair has double tubing at the sides

and a lacquered sheet metal base. The legs unintentionally resemble

horse hooves. Perriand took this and ran with it, finding pony skin

from Parisian furriers to cover the chaise. Perriand wrote in a

memoir, "While our chair designs were directly related to the

position of the human body...they were also determined by the

requirements of architecture, setting, and prestige". With a

chair that reflects the human body (thin frame, cushion/head) and has

decorative qualities (fabrication, structural qualities) they

accomplished this goal. It wasn't instantly popular due to its formal

simplicity but as modernism rose, so did the chair's popularity.

In 1940 Perriand

traveled to Japan as an official advisor for industrial design to the

Ministry for Trade and Industry. While in Japan she advised the

government on raising the standards of design in Japanese industry to

develop products for the West. On her way back to Europe she was

detained and forced into Vietnamese exile because of the war.

Throughout her exile she studied woodwork and weaving and also gained

much influence from Eastern design. The Book of Tea which she read at

this time also had a major impact on her work and she referenced it

throughout the rest of her career.

In the period after

World War II (1939–45) there was increased interest in using new

methods and materials for mass production of furniture. Manufacturers

of materials such as formica, plywood, aluminum, and steel sponsored

the salons of the Société des artistes décorateurs. Designers who

exhibited their experimental work at the salons in this period

included Perriand, Pierre Guariche, René-Jean Caillette, Jean

Prouvé, Joseph-André Motte, Antoine Philippon and Jacqueline Lecoq.

Charlotte Perriand took part in the design of the ski resorts of Les

Arcs in Savoie. In the 1950s she designed for various corporate

service spaces. Perriand's main goal as a designer was to develop

affordable, functional, and appealing furniture for the masses.

Some of her work

includes:

Meribel ski resort

The League of

Nations building in Geneva

the remodeling of

Air France's offices in London, Paris, and Tokyo

Charlotte Perriand

collaborated with Jean Prouvé through the rest of her career.

No comments:

Post a Comment