Dumfries House is a Palladian country house in Ayrshire, Scotland. It is located within a large estate, around 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) west of Cumnock. Noted for being one of the few such houses with much of its original 18th-century furniture still present, including specially commissioned Thomas Chippendale pieces, the house and estate is now owned in charitable trust by the The Great Steward of Scotland's Dumfries House Trust, who maintain it as a visitor attraction and hospitality and wedding venue. Both the house and the gardens are listed as significant aspects of Scottish heritage.

The estate and an earlier house was originally called Lochnorris, owned by Craufords of Loudoun. The present house was built in the 1750s for William Dalrymple, 5th Earl of Dumfries, by John Adam and Robert Adam. Having been inherited by the 2nd Marquess of Bute in 1814, it remained in his family until 7th Marquess decided to sell it due to the cost of upkeep.

Due to its significance and the risk of the furniture collection being distributed and auctioned, after three years of uncertainty, in 2007 the estate and its entire contents was purchased for £45m for the country by a consortium headed by Charles, Prince of Wales, including a £20m loan from the Prince's charitable trust. The intention was to renovate the estate to become self-sufficient, both to preserve it and regenerate the local economy. As well as donors and sponsorship, funding is also intended to come from constructing the nearby housing development of Knockroon, a planned community along the lines of the Prince's similar venture, Poundbury in Devon.

The house duly re-opened in 2008, equipped for public tours. Since then various other parts of the estate have been re-opened for various uses, to provide both education and employment, as well as funding the trust's running costs.

The estate was finally purchased as a whole after Charles, Prince of Wales heard of the campaign after the writer and campaign member James Knox made an impassioned impromptu speech at one of the Prince's bi-annual conservation conferences at Holyrood House in Edinburgh. On 27 June 2007 it was announced that a consortium headed by the Prince and including various heritage charities and the Scottish Government (contributing £5m) had raised £45 million to purchase the house and contents (along with its roughly 2,000-acre (8.1 km2) estate) and to endow a trust for maintaining it. The trust is called "The Great Steward of Scotland's Dumfries House Trust" — a reference to the title Great Steward of Scotland held by Charles in his role as Scottish heir apparent. A major element of the financial package was a £20m loan backed by The Prince's Charities Foundation. It was reported that the contents of the house had already been removed, and were being transported to London when the sale was agreed.

The trust's intended model is to have the estate become a self-sufficient enterprise, in the process revitalising the local economy. The project was to be achieved through donation and sponsorship of various renovation projects around the estate, as well as through revenues from the construction of an 'eco-village' in the grounds, a planned community called Knockroon.

The breaking in 2008 of the global financial crisis had a major impact on the project, affecting the prospects for the Knockroon development and thus the recouping of the £20m loan, for which the Prince faced much media criticism for putting the charities other projects at risk for what was seen as a vanity project, prompting a response in 2010 describing the risk as manageable and fully covered. After switching to a model of private and corporate fund raising, the £20m loan was repaid by 2012, with a further £15m backing having been raised for the various renovation projects and ongoing maintenance bill for the estate.

Following restoration, Dumfries House itself opened to the public for guided tours on 6 June 2008. From mid-2009, supermarket chain Morrisons began funding the restoration of the meat and dairy farm attached to the estate, both to become a research and education tool into sustainable farming methods, but also with the intention of it becoming profitable by 2014, part of the chain's vertically integrated supply chain. Renovation of the former coach house and associated stable block began in winter 2010. It reopened in 2011 as a catering facility, as both a visitor cafe and bistro dining facility. The first phase of the Knockroon village opened in May 2011. In October 2011 work started to clear the area that used to be the Walled Garden, which had fallen into disuse and become overgrown. In April 2012, the six bedroomed luxury guest house Dumfries House Lodge opened, to provide guest accommodation for wedding parties and other events. It was created by renovating a derelict farm building on the estate. The estate's former water powered sawmill has been renovated to full working order, and with the addition of a larger workshop building, has re-opened as the Sawmill Building Skills Centre, a traditional skills education facility.

The Prince of Wales continues to support Dumfries House. In September 2012, with the Duchess of Cornwall and Alex Salmond, he attended Ladies' Day at Ayr Racecourse in aid of the Trust.

Dumfries House: a Sleeping Beauty brought back to life by the Prince of Wales

Saved by Prince Charles from the auctioneer's hammer, Dumfries House - a time capsule of 18th-century furnishing - has been restored to its former glory

By Annabel Freyberg 27 May 2011 in The Telegraph / http://www.telegraph.co.uk/property/8533968/Dumfries-House-a-Sleeping-Beauty-brought-back-to-life-by-the-Prince-of-Wales.html

Dumfries House has been portrayed as an 18th-century Sleeping Beauty. Adam-designed and Chippendale-furnished, it remained untouched for 250 years, so the story goes, before being kissed by a prince and startled into trembling new life. Astoundingly, this fairy tale is largely true.

Until this gem of an estate was 'saved for the nation’ in June 2007, few people even knew of its existence. Yet its contents, dating from the mid-1750s, when it was built by the 5th Earl of Dumfries, include at least 50 pieces by the great British furniture maker Thomas Chippendale – some specially made for the house – along with the finest surviving collection of carved Scottish rococo furniture.

It took a last-minute pledge of £20 million from the Prince of Wales, allied to £25 million raised from other sources, to prevent its contents being dispersed around the world. In fact, less than two weeks before the threatened sale at auction by its owner, the 7th Marquess of Bute, much of the furniture had been packed up, ready to be taken to London. It was a close call.

No time has been wasted since then to make best use of the house’s riches. Its infrastructure has been improved at a cost of £1.5 million, rooms re-presented and gentle conservation embarked on (also to the tune of £1.5 million – much of it donated by individuals keen to see particular works restored, with a further £1.5-2 million spent on outbuildings for imminent use).

The scale of work is a curator’s dream,’ Charlotte Rostek, Dumfries House’s curator since April 2008, says. 'And we have been able to carry out a level of conservation work of which most other museums and stately homes can only dream.’

Indeed, there has never been a historic house project like it. A crucial element is the desire to kick-start regeneration in this impoverished part of east Ayrshire – a version of the Guggenheim effect, perhaps, whereby dramatically designed museums have drawn millions into previously depressed towns such as Bilbao in Spain.

'It’s not solely about Adam and Chippendale, it’s about jobs,’ confirms the writer James Knox, an Ayrshire neighbour who was involved in the campaign to save the house. 'And giving people a sense of belief in themselves locally, and being heard.’ This is not merely talk. When, shortly after the fate of Dumfries House was announced, the Prince of Wales visited the nearby former mining town of Cumnock, he was mobbed in the street by ecstatic long-term unemployed people.

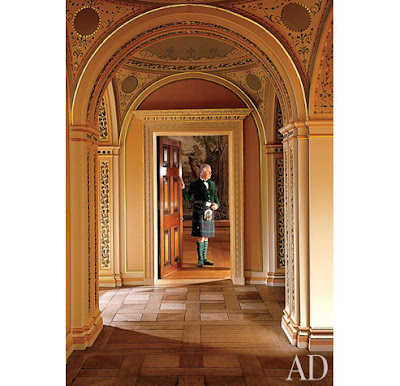

Today, in sunny late April, visitors to Dumfries House are welcomed by clouds of pink blossom from two magnificent cherry trees on the drive. The shorthorn cattle grazing in front of the house are part of the 900-acre farm partnership between Dumfries House and Morrisons supermarket.

The Prince – or the Duke of Rothesay, to give him his Scottish title – has just dropped in to mark the new season’s opening to the public. (He had never been here when he contributed millions to saving the estate, but has made up for it since by visiting every couple of months, and even has a bedroom in the house.)

There has been a major winter overhaul over five breakneck (and freezing) months while the house was closed to the public: 1930s and even some Edwardian electrics have been replaced, the building replumbed from top to bottom, and a vast biomass boiler installed, which will control temperature and humidity levels and be self-sustaining. 'Furniture is susceptible more to humidity levels than temperature,’ Rostek says.

In the grounds, builders are putting the final touches to the new cafe in the converted Coach House. In the 600-acre woods, a team from the East Ayrshire Woodland Group has been working on a programme of replanting for the past 18 months, financed by the Government’s Future Jobs Fund. Fuel for the biomass boiler will come from the estate’s trees; it needs to be dried for a year first, then chipped.

Near Cumnock, a new model eco community – in some respects a Scottish Poundbury – is taking shape on Dumfries estate land. Knockroon, 'a walkable neighbourhood encouraging social interaction and a strong sense of community’, has been designed by the architects Lachlan Stewart and Ben Pentreath for the Princes Foundation for the Built Environment, and is 'inspired by local architecture that was built between the late 17th and mid-19th centuries’.

It is being overseen by Andrew Hamilton, who for the past 20 years has coordinated the Poundbury project, and was in the Prince’s mind from the beginning of his negotiations over Dumfries House. Planning permission for 600 homes was granted in January.

There is much more in the pipeline: traditional building skills workshops in the old saw mill; an educational food centre for children; a conference centre in the stable block; the restoration of the walled garden; even a hotel in the grounds. Yet the atmosphere of the 2,000-acre park is peaceful, as are the revitalised but not over-primped interiors.

Rostek acknowledges that though the house’s treasures are only one aspect of the whole picture, they have inevitably been the focus. It is a rich seam for scholars and restorers alike.

Most exotically, the flamboyant Chippendale four-poster is back from London where it was newly redressed in its original style of blue silk finery, thanks to a feat of archival detective work. While Christie’s insisted that the hangings were originally green, Rostek pored over 18th-century invoices to discover that they were actually blue. The textile historian Annabel Westman then oversaw about 20 craftsmen in three different specialist workshops as they restored the intricately carved cornice and covered it skin-tight in blue silk damask.

A tour of the formal ground-floor rooms reveals the extent of carefully researched housekeeping achieved over the past four years. In the Blue Drawing Room, the first Adam room the paying public come to, a suite of Chippendale elbow chairs and sofas has been reupholstered in a specially woven startling blue damask by Humphries Weaving, and the ruched curtains have been resplendently remade in the same fabric by the expert curtain maker Janette Read (who has redone the curtains throughout the house).

The surprisingly modest padauk Chippendale bookcase – the most valuable piece of furniture in the house (bought for £47 5s in 1759 and valued at £4 million in 2007) – was restored in situ over three weeks by the Edinburgh furniture restorer James Hardie.

The bold Axminster carpet covering the entire drawing-room floor dates from 1759, and is one of the first the company ever produced. Between the windows hang a pair of joyous and intricate pier glasses by William Mathie of Edinburgh (he, Francis Brodie and Alexander Peter are the three great Scottish cabinetmakers, all represented here). On the wall opposite is a pair of full-length Raeburn portraits of members of the family who lived here in the second half of the 18th century.

When Rostek is asked to give talks about the furniture of Dumfries House, she always declares that she can’t do it without reference to the people who lived here. These portraits are a good starting point. They depict the strikingly kind-looking Patrick McDouall-Crichton, 6th Earl of Dumfries, with his ward Flora, Countess of Loudon, and Margaret, his wife, with their daughter, Lady Elizabeth Penelope Crichton. Both Flora and Elizabeth are relevant to the story.

In 1768 Patrick inherited Dumfries House from his uncle, the 5th Earl (his portrait hangs in the Pink Dining Room), who had built and furnished it in 1754-9, commissioning the architects Robert and John Adam, and using pink sandstone quarried on the estate.

Elizabeth married the eldest son of the 1st Marquess of Bute in 1792 and had two sons. Soon afterwards, her husband was killed in a riding accident, aged 27, and she died three years later. (The story of the Butes is littered with early deaths.) For the next few years the boys were raised by their maternal grandparents, alongside Flora.

The eldest boy, John, was nine when his grandfather died in 1803, and 20 when his other grandfather died, and he became the 2nd Marquess of Bute. From that point on, Dumfries House became the family’s secondary home, with Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute their main residence.

This is one of the astonishing facts about Dumfries House and one of the reasons its original interiors are so well preserved – and remained a secret for so long. For 250 years the family who owned the estate took good care of it, constantly upgrading, modernising and making it more comfortable, but only rarely living there. There were certainly changes over the years (the Axminster was 'cleaned and shaved’ in 1846, for example; the Chippendale bed refurbished in 1869), but the original scheme remained intact.

It was the 2nd Marquess who made the family fortune by turning the fishing village of Cardiff into a major port. (This wealth meant that the family never needed to sell Dumfries House.) His first marriage was childless, but by his second wife, Sophia Hastings – the daughter of Flora, his childhood companion – he fathered a son at the age of 52, then died when the child was six months old. Dumfries House fell into another slumber.

The 3rd Marquess continued to develop Cardiff, but is best known as a spectacular patron of the arts, responsible for recreating Cardiff Castle and Castell Coch to the north of Cardiff. He made substantial additions to Dumfries House too, installing a Turkish bath (now the Billiard Room) and a Byzantine chapel (he was a devout Catholic convert). In 1877 Mount Stuart burnt down, and while it was being built anew as a gothic-revival fantasy, the 3rd Marquess and his family spent more time at Dumfries House. In the 1890s he hired the leading Scottish Arts and Crafts architect Robert Weir Schultz to build a pair of large wings at the back – doubling the house in size without making this apparent from the symmetrical Palladian front. He described Dumfries House as the 'homeliest’ of his many homes.

While the 4th Marquess finished the extensions started by his father, the last person to call Dumfries House home was Lady Eileen Bute. The wife of the 5th Marquess, she came here as a young bride in 1932.

The family moved out during the Second World War when the house was requisitioned by the Army, but she returned after her husband died in 1956 (aged 49), and was popular with locals until her death in 1993.

'She had a group of friends known as the Ayrshire widows,’ James Knox says. 'They were all very good-looking women and had a lovely time chain-smoking, drinking whisky and playing poker in those wonderful rooms. They were mad on racing and Lady Eileen would have huge house parties for the Ayr races.’

After her death, Dumfries House went back to sleep. A few months later her son, the 6th Marquess of Bute, died, and his son, the racing driver Johnny Dumfries, now the 7th Marquess (and known as Johnny Bute), was hit with double death duties. The sale of Dumfries House looked inevitable.

In 1994 he approached the National Trust for Scotland. They weren’t enthusiastic – partly, it appears, because Paxton House, another Scottish Adam house also with Chippendale furniture, had recently opened to the public. By now Johnny Bute was fully occupied with opening Mount Stuart to the public for the first time (in 1995), and for nearly a decade nothing happened. Bute even put a new roof on Dumfries House, for which the current custodians are extremely grateful.

The National Trust for Scotland was offered the chance to acquire Dumfries House again in 2004, and negotiations dragged on, with Sotheby’s brought in to value the contents for the trust, and Christie’s for the Marquess (later, Bonhams arrived on behalf of the council). Such was the scale of the task that Christie’s experts spent 18 months cataloguing the collection. When negotiations with the trust failed, an exasperated Johnny Bute was forced to look at alternatives, and in April 2007 he instructed Savills to sell the house and Christie’s its contents.

For several years, a number of art lovers had been monitoring the situation at Dumfries House. As soon as its sale was announced they launched a public appeal to preserve it as an independent charitable trust under the auspices of Save Britain’s Heritage. Generous funding was lined up from charitable bodies such as the Monument Trust, the Art Fund and the Garfield Weston Foundation. But it still wasn’t enough.

The turning point came in May 2007, when Historic Scotland (the Scottish equivalent of English Heritage) declined to support the campaign financially and declared that Dumfries House could not be saved. Every two years, the Prince of Wales convenes a conference at Holyrood House in Edinburgh for the great and the good of the conservation world in Scotland.

James Knox used the opportunity to make an impassioned impromptu speech about the importance to the region of preserving Dumfries House. It was not a popular move. 'Nobody really wanted to talk about Dumfries House,’ Knox says. 'They thought it was too big, too expensive, too impossible, too controversial. I sat down to stony silence.’

But the campaign had caught the attention of the Prince, who wanted to know what he could do to help. With only weeks before the sale of house and contents, the Prince took a huge risk and arranged a loan of £20 million secured against the Prince’s Charities Foundation.

The Scottish government came on board to the tune of £5 million, and the estate was handed over to the newly formed Great Steward of Scotland’s Dumfries House Trust (after one of the Prince’s other Scottish titles). The Prince likes to quote the 5th Earl of Dumfries, who declared of his decision to build the house, '’Tis certainly a great undertaking, perhaps more bold than wise, but necessity has no law’, adding, 'I felt rather the same some 250 years later.’

The Prince’s involvement is hands-on. Last month he met the first couple planning to marry at Dumfries House – a new moneyspinner – and his watercolours line what will be the groom’s room. He was involved in the design of a new sunken garden, and the Pink Dining Room is likely to stay that hue for the moment (it was painted pink in about 1955) because it is his favourite room.

Dumfries House opened to the public in June 2008, and is beginning to establish itself on the tourist trail (it is 15 miles away from the popular Culzean Castle), and new events are springing up locally too – last weekend saw the first Boswell Book Festival at neighbouring Auchinleck House.

'We have a five-year plan, and we aim to be self-sustaining,’ Rostek says. 'We’re not cash rich, and we don’t have an endowment, but the Prince makes it work through his leadership. It’s a journey from an idea to reality – it has to work and pay its way.’

dumfries-house.org.uk

.jpg)