The Glamour Boys by Chris Bryant review – the

rebels who fought for Britain

The fascinating story of 10 courageous gay MPs who saw

clearly that war was inevitable and were prepared to take a stand against

appeasement

Simon

Callow

Fri 6 Nov

2020 07.30 GMT

In The

Glamour Boys, Chris Bryant sets out to bring to light the remarkable and in

some cases heroic contribution of gay MPs to Britain’s involvement in the

second world war. It is not an unknown story: five years ago Michael Bloch

covered it in his racy, rather tabloid Closet Queens. But Bryant, the Labour MP

for Rhondda, and gay himself – indeed something of a poster boy for the gay

cohort in today’s parliament – offers a much more detailed, infinitely more

complex, account of the 10 “queer, or nearly queer” members of parliament who

took an increasingly forthright stand against Neville Chamberlain’s policy of

appeasing the German, Italian and Spanish dictators of the interwar years,

risking their careers and in some cases losing their lives in battle. Bryant

makes large but not excessive claims for them: “Had it not been for the Glamour

Boys’ campaign against Chamberlain we would never have fought, let alone won,

the second world war.”

In fact,

“the 17-strong Glamour Boys”, as the anti-appeasement faction in the Commons

were nastily dubbed by Chamberlain, were by no means all gay, including as they

did Harold Macmillan, Anthony Eden, Duncan Sandys, Leo Amery and, of course,

Winston Churchill. Bryant’s queer group of 10 were Robert Boothby, Harold

Nicolson, Rob Bernays, Victor Cazalet, Harry Crookshank, Jack Macnamara, Ronnie

Cartland, Ronnie Tree, Philip Sassoon and Jim Thomas. This uncommonly talented

group were for the most part Conservatives, though in the unfathomably complex

party arrangements of the interwar years, at any one time they might sit with

National Liberal or National Labour members.

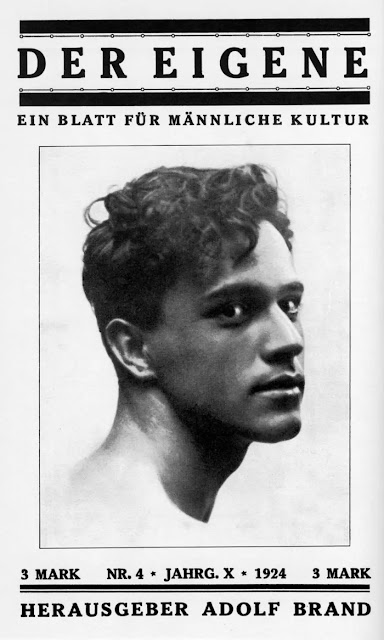

From the

moment Hitler came to power in 1933, the Glamour Boys saw clearly that war was

inevitable and, tentatively to begin with, then with increasing directness,

they said so, incurring the opprobrium both of their fellow parliamentarians

and of the heavily pro-appeasement press. Many of them had direct knowledge of

Germany; before the Nazis came to power and even after, the gay MPs, like many

other homosexual men, had made a beeline for Weimar Berlin – that “bugger’s

daydream”, as WH Auden put it – relishing a degree of sexual freedom

unimaginable in Britain.

Bryant

notes the courage of these men, not only in adopting an unpopular stance in

parliament, but in standing as MPs at a time when homosexuality was savagely

punished. A number of them were married, some bisexual “or somewhere in

between”, but all of them, if discovered having sex with another man, could

have found themselves brutally prosecuted. Worse even than the punishment was

the public obloquy: threatened with a court of inquiry in 1902, a lauded Boer

war hero, Major-General Sir Hector Macdonald, had chosen to kill himself.

Despite all

of this, gay men still managed to enjoy themselves, and each other. Bryant

paints a kaleidoscopic picture of the clandestine gay scene in the London of

the 1930s. The area around Piccadilly Circus was Queer Central – the Trocadero,

the Criterion Bar, the Lyons Corner House, the Jermyn Street Baths and clubs

such as Rendezvous where one could meet, in the evocative phrase of the actor

and writer Emlyn Williams, “well-behaved male trash”; there was even a gay

guide book (deliciously called For Your Convenience). But danger was ever

present, not least in the form of pretty policemen. Arrests were frequent, and

neither wealth nor class was any protection.

Bryant notes the courage of these men, in standing as

MPs at a time when homosexuality was savagely punished

Meanwhile,

the world was agog at the spectacular rise and fall of the homosexual Ernst

Röhm, scar-faced leader of the Sturmabteilung, the Nazi paramilitary wing. The

Night of the Long Knives, in which he and his cohorts were annihilated, quickly

confirmed the end of any semblance of sexual toleration; a new law,

criminalising the “promotion of homosexuality” (sound familiar?) was enacted.

Between 1933 and 1945, 100,000 gay men were arrested; from as early as 1929 the

party paper, the Völkischer Beobachter, had conflated homosexuality and

Judaism: one of the many “evil instincts” that characterised Jews, the paper

claimed, was that they tried to promote sexual relationships between siblings,

men and animals, and men and men. Such “perverted crimes”, the paper concluded,

should be punished by banishment or hanging.

These

developments were enthusiastically received in Britain. The Times demurely

welcomed the fact that “the Führer has started cleaning up”. That same year,

1934, Lord Rothermere’s Daily Mail came out for Oswald Mosley’s British Union

of Fascists: some of the staff even went to work in black shirts, while the

Sunday Pictorial ran a competition to find the nation’s prettiest female

fascist. Antisemitism was universal: when Bernays, whose great-grandfather had

been Jewish, stood for parliament, his campaign posters were plastered over

with stickers saying “JEW”. In the House of Commons, Robert Tatton Bower

bellowed at the London-born Labour MP Manny Shinwell: “Go back to Poland”. In a

debate, Sassoon was told by the Clydesider Labour MP David Kirkwood that he was

no Briton, but “a foreigner”.

Opposition

to government was tightly policed by Chamberlain’s master of dirty tricks, Sir

Joseph Ball, a key mover in forging and disseminating the Zinoviev letter,

which lost Labour the 1924 election. A deeply sinister figure, he fed the whips

gobbets of scandal, which they used to control potentially rebellious MPs; he

it was who masterminded Eden’s resignation as foreign secretary and then

ensured that it was downplayed in the papers. The gay Glamour Boys had to be

very careful. They were, as it happens, far from being inherently radical:

after being shown round Dachau in 1933, Cazalet wrote in his diary: “Great fun.

I visit the ‘Concentration Camp’. It was not very interesting. Quite well run,

no undue misery or discomfort.”

Typically

it was only when calamity befell someone of their acquaintance that their

personal feelings led to political action: Cazalet’s friend, the great German

tennis player Gottfried von Crammok, had an affair with the Jewish actor

Manasse Herbstok, and they both seemed imperilled, so Cazalet leapt into

action, very effectively. Likewise Nicolson managed to intervene on behalf of

the German translator of the books of his wife, Vita Sackville-West. From these

experiences they learned which way the wind was blowing, and quite how savage

and unrelenting that wind was.

The area around Piccadilly Circus was Queer Central,

but danger was ever present, not least in the form of pretty policemen

They all,

to a greater or lesser degree, piled pressure on the government, who in the

face of Hitler’s blatant war-mongering finally had to concede that he could be

appeased no longer. A number of the 10 – Macnamara and Cartland in particular –

fought and died bravely; Bernays’s plane was lost in action, and Cazalet perished

flying with the Polish prime minister in exile, Wladyslaw Sikorski, in still

mysterious circumstances. They are commemorated in a carved memorial behind the

Speaker’s chair in parliament, but, as Bryant observes, they are largely

unknown.

Not any

longer, it is to be hoped: he has done them honour, reminding the world that

gay people are every bit as various as heterosexuals. He has handled the

difficult form of group biography skilfully, using a great deal of never before

published material, and introducing us to a number of little known figures,

notably Cartland and the gallant and dashing Macnamara. The one thing Bryant is

unable to explore is the intimate lives of these people, because they avoided

at all costs confiding their emotional and indeed carnal experiences to paper,

so neither letters nor diaries give us even glimpses of their deepest feelings.

There is a

rare light-hearted section of the book. Cazalet was tasked with recruiting for

the 83rd Light Anti-aircraft Battery, with 10 officers and ranks. He

interviewed and recruited many of the men personally – often at the Ritz or the

Dorchester. Nicolson’s son, the art historian Benedict, one of many gay

recruits, said of it that “it’s so civilised, friendly, incompetent”. Cazalet inspected

the men every week, sent his regards to their parents or lovers, and chatted

with everyone before getting back into his Rolls-Royce, saying: “I have to

hurry. I’m having tea with Queen Mary.” Unsurprisingly, the battery acquired a

reputation. Some called it “the Monstrous Regiment of Gentlemen”, others “a

sissy AA battery”, and Philip Toynbee was keen to join because “it led to all

sorts of ‘amusing things, such as well-known pansies mincing into the Café

Royal in battle-dress’,” but was prevented by his father-in-law from joining

what the old gent described as “a bugger’s battery”. Delicious stuff. Needless

to say, when it came to actual combat, they fought like lions.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment