The Hon. Daisy

Fellowes (née Marguerite Séverine Philippine Decazes de Glücksberg)

(29 April 1890, Paris – 13 December 1962, Paris),[ was a celebrated

20th-century society figure, acclaimed beauty, minor novelist and

poet, Paris Editor of American Harper's Bazaar, fashion icon, and an

heiress to the Singer sewing machine fortune.

She was born in

Paris, the only daughter of Isabelle-Blanche Singer (1869–1896) and

Jean Élie Octave Louis Sévère Amanieu Decazes (1864–1912), the

3rd Duke Decazes and Glücksberg. Her maternal grandfather was Isaac

Merritt Singer, the American sewing-machine pioneer. After her

mother's suicide, she and her siblings were largely raised by their

maternal aunt Winnaretta Singer, Princess Edmond de Polignac, a noted

patron of the arts, particularly music.

Her first husband,

whom she married 10 May 1910 in Paris, was Jean Amédée Marie

Anatole de Broglie Prince de Broglie (born in Paris on 27 January

1886). He reportedly died of influenza on 20 February 1918 while

serving with the French Army in Mascara, Algeria, though malicious

observers gossiped that he actually committed suicide as a result of

his homosexuality having been exposed.

Their country estate

was Compton Beauchamp House were they raised three daughters:

Princess Emmeline

Isabelle Edmée Séverine de Broglie (Neuilly, 16 February 1911 –

Onez, Switzerland, 10 September 1986). Married to Marie Alexandre

William Alvar de Biaudos, Comte de Castéja (Paris, 6 April 1907 –

Paris, 6 July 1983) in Neuilly, 8 November 1932. Accused of

collaboration during World War II, Emmeline de Castéja spent five

months in the prison at Frèsnes, France.

Princess Isabelle

Marguerite Jeanne Pauline de Broglie (Lamorlaye, 27 July 1912 –

Geneva, 18 July 1960). Married to Olivier Charles Humbert Marie,

Marquis de La Moussaye (La Poterie, 26 Mars 1908 – Paris, 20

October 1988) in Neuilly, 3 June 1931. Divorced in Paris, 13 April

1945. Isabelle de La Moussaye was a novelist.

Princess Jacqueline

Marguerite de Broglie (Paris, 5 January 1918 – Crans-Montana,

Valais 26 February 1965). Married to Alfred Ignaz Maria Kraus

(Sarajevo, 28 November 1908–) in Neuilly, France, 6 October 1941.

Divorced in Münster 3 February 1958. After her husband—a Siemens

electronics senior manager who served as a counter-espionage agent

with the [Abwehr]—was accused of betraying members of the French

Resistance during World War II to protect his wife, also a member of

the Resistance, Jacqueline Kraus had her head shaved as punishment.

Of her Broglie

children, the notoriously caustic Fellowes once said, "The

eldest, Emmeline, is like my first husband only a great deal more

masculine; the second, Isabelle, is like me without guts; [and] the

third, Jacqueline, was the result of a horrible man called Lischmann

...."

Her second husband,

whom she married on 9 August 1919 in London, was The Hon. Reginald

Ailwyn Fellowes (1884–1953), of Donnington Grove. He was a banker

cousin of Winston Churchill and the son of William Fellowes, 2nd

Baron de Ramsey.

They had one child,

Rosamond Daisy Fellowes (1921–1998). She married in 1941 (divorced

1945), as her first husband, Captain James Gladstone, and had one

son, James Reginald (born 1943). He married Mary Valentine Chiodetti

in 1965. She married in 1953 (divorced), as her second husband,

Tadeusz Maria Wiszniewski (1917–2005); they had one daughter, Diana

Marguerite Mary Wiszniewska (born 1953).

Among Fellowes's

lovers was Duff Cooper, the British ambassador to France. She also

attempted to seduce Winston Churchill, shortly before marrying his

cousin Reginald Fellowes, but failed.

Fellowes wrote

several novels and at least one epic poem. Her best-known work is Les

dimanches de la comtesse de Narbonne (1931, published in English as

"Sundays"). She also wrote the novel Cats in the Isle of

Man.

She was known as one

of the most daring fashion plates of the 20th century, arguably the

most important patron of the surrealist couturier Elsa Schiaparelli.

She was also a friend of the jeweller Suzanne Belperron. She was also

a longtime customer of jeweller Cartier.

Daisy Fellowes died

at her hotel particulier on the Rue de Lille number 69, Paris

The Most wicked woman in High Society

She

lived on grouse, cocaine and other women's husbands. As her gems are

sold at Sotheby's, the jaw-dropping story of... the most wicked woman

in High Society

Daisy

Fellowes was the living embodiment of Thirties chic

She

was a voracious man-eater, who’d steal her daughters’ boyfriends

and seduce her best friends’ husbands

By CHRISTOPHER

WILSON

She was rich, ugly,

dissolute and ‘the destroyer of many a happy home’ as one

ex-lover bitterly put it.

She did her best to

seduce a married Winston Churchill and when that failed, wed his

cousin. She lived on a diet of morphine and grouse, with the

occasional cocktail thrown in.

The colour Shocking

Pink was created for her — and how she loved to shock! If it wasn’t

morphine then it was opium or cocaine, and she loved nothing better

than discussing her private collection of leather-bound volumes of

pornography.

When it came to sex

she was a voracious man-eater, who’d steal her daughters’

boyfriends and seduce her best friends’ husbands.

Yet Daisy Fellowes

was also the living embodiment of Thirties chic, a style icon who

inspired designers Chanel and Schiaparelli and who wore so many

jewels they weighed her tiny body down.

Heiress to the

Singer sewing machine empire, she was ‘the very picture of

fashionable depravity’, according to her rival Lady Diana Cooper.

And Lady Diana should know — Daisy bedded her husband and

determinedly remained his mistress for 17 years.

The uber-rich Mrs

Fellowes was also the greatest collector of fine jewellery the 20th

century ever saw. Her rapacious and salacious life was remembered

this week when one of her pieces — a crystal and pearl clip — was

among the highlights of Sotheby’s spring gem sales.

Though she became a

central part of Mayfair society during the inter-war years, buying up

the friendship of royalty, ministers, peers and moguls, Daisy was in

fact half-French, half-American.

Her mother was

Isabelle Singer, daughter of the inventor of the first commercially

successful sewing machine, while her father was a French aristocrat,

the Duc Decazes.

At 19, she was

married off to Prince Jean de Broglie, but the relationship fell

apart when she found him in bed with the chauffeur.

Marriage, however,

had unlocked an inextinguishable sexuality and soon she was to be

found in the Ritz Hotel in Paris desperately trying to bed Winston

Churchill, then a young MP.

According to

Winston’s later private secretary, Jock Colville: ‘She was a

wicked but attractive woman who, according to Mrs Churchill, tried to

seduce her husband shortly after their marriage. It was unsuccessful

and she was forgiven, even by Clementine.’

By now, Daisy had

three children. ‘The oldest, Ermeline, is like my first husband

only a great deal more masculine. The second, Isabelle, is like me,

only without guts; the third was the result of a horrible man called

Lischmann,’ she spat when someone gently inquired about them.

Nonetheless she had

a sneaking fondness for children — but only at a distance. One day

strolling in a park, she exclaimed: ‘Oh look at those pretty little

girls. Aren’t they beautifully dressed! We must go and ask the

nurse whose they are.’ Walking over, Daisy duly asked: ‘Whose

lovely little children are these?’

‘Yours, Madam!’

snapped the nurse.

‘She was

fascinating and I suppose wicked; her wickedness was on a scale that

it had its own distinction,’ declared David Herbert, son of the

Earl of Pembroke. Again, he should know — Daisy threw herself at

his bumbling father in the hope of becoming an English countess.

After a brief

dalliance in Paris, Pembroke realised what a lightning storm he’d

walked into and tried to back away.

Her brother, now

having succeeded their father as the Duc Decazes, claimed her

reputation had been damaged by this rejection and challenged the

bewildered Pembroke to a duel. The peer scuttled back across the

English Channel and Daisy returned to flicking through the pages of

Burke’s Peerage for a new husband.

He was soon to

arrive. But first Daisy decided that a little remodelling was in

order. It was not sufficient that she was rich, she must have

breeding and looks to match.

After commissioning

a portrait of herself she’d been appalled by the result and set to

work. She had a nose-job, without anaesthetic, threw away her entire

wardrobe and started to consult couturiers. And she began, very

seriously, reading books.

Daisy described

herself as always being ‘on the scent’ of new conquest

The Daisy that the

Hon. Reggie Fellowes met and married was a very different article to

the teenager who’d wed the Prince de Broglie.

Her new husband was

rich, a banker, the son of the second Baron de Ramsey, connected to

Winston Churchill through the Dukes of Marlborough, and a decidedly

good egg. The couple made their home in France, with frequent visits

to London.

In the milieu she

now inhabited, sexual freedom was obligatory once she’d secured the

marriage by having a child with Fellowes. A friend recalled Daisy in

Monte Carlo with her lover Fred Cripps, later Lord Parmoor: ‘She

and Fred tracked Reggie down to a brothel and through a rough glass

window watched him perform with a poll [prostitute]. He didn’t know

of course, but they told him afterwards.’

Rich, wayward,

uncontrollable, her marriage remained a success despite her

determination to cuckold as many wives as possible. She described

herself as always being ‘on the scent’ of new conquest. ‘It’s

a thrilling feeling,’ she confessed, ‘like tasting absinthe for

the first time. Soon the man asks: “When may I come to tea?” —

that’s when I sharpen the knife.’

The painter Sir

Francis Rose was both fearful and admiring: ‘She’s as dangerous

as an albatross,’ he declared. Another lover, Alfred Duff Cooper,

father of writer John Julius Norwich, described how smoking opium

before sex lowered her inhibitions to the point of extinction.

While in Paris she

mixed with the new, thrilling art movement which included the writer

Jean Cocteau and Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes.

When Diaghilev’s star ballerina complained of a headache, Daisy

produced ‘a white powder which worked wonders’. It was cocaine,

her new drug of choice.

The composer and

painter Lord Berners was similarly introduced to the dubious delights

of cocaine by Daisy and was soon serving it during decorous

tea-parties at Faringdon, his Oxfordshire stately home.

But by the time Duff

Cooper was Britain’s ambassador in Paris, at the end of World War

II, Daisy had moved on again.

Diana Cooper learned

from her friendly rival — she tolerated, even encouraged, her

husband’s on-off affair with Mrs Fellowes — how to jazz up a

boring drinks party. ‘Just pour Benzedrine [an amphetamine] into

the cocktails, darling!’

Daisy kept two

yachts on the go, crewed and ready for action, in the Mediterranean.

Her hospitality was lavish, but it came at a price.

Society photographer

Cecil Beaton jumped ship after a brutal few days cooped up with his

hostess under azure-blue skies: ‘Daisy has been impossible. She

bullies one person, keeping the others on her side until it’s time

to bully the next person. She is spoilt, capricious, and wicked.’

Other guests on her

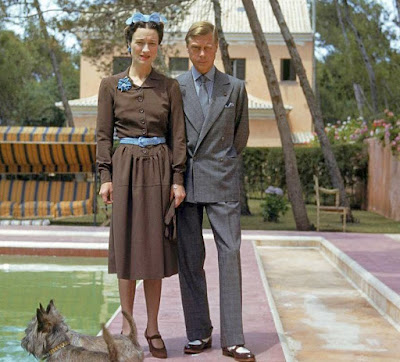

bigger yacht, the Sister Anne, included the Prince of Wales and a

then unknown American, Wallis Simpson. The romance between the

soon-to-be King and his divorcee was still fresh, ‘otherwise, make

no mistake, Daisy would have gone for him’, observed a fellow

passenger.

It was Daisy's

clothes — and her jewels — that people talked about most

It was 1935 and the

world would have to wait another year to discover who the Prince

loved enough to give up his throne for — but in the calm waters of

the Mediterranean Daisy Fellowes was already privy to the country’s

most devastating secret.

All these things,

good and bad, should have made Daisy the focus of Society’s

attention, but it was her clothes — and her jewels — that people

talked about most.

There were diamonds,

emeralds, sapphires, rubies, outside the Crown Jewels, there was

nothing to match them. The big jewellers of the day, Cartier, Van

Cleef and Arpels, were in seventh heaven for she never stopped

shopping.

Vogue magazine

saluted her ‘for daring to be different’. At the Ritz, diners

climbed on chairs to get a glimpse of her Schiaparelli monkey-fur

coat embroidered in gold, and she shocked the public by wearing a

Surrealist hat shaped like a high-heeled shoe.

It was then that

Schiaparelli invented ‘shocking pink’ for Daisy, and she wore it

with panache — a lobster dress, or a black suit with pink lips for

pockets.

Alas, all legends

fade and World War II helped reshape society. Daisy was getting

older, while husband Reggie was in a wheelchair.

She was deeply

shamed to discover that her daughter, Jacqueline, who stayed in

France and heroically worked for the French Resistance, had

unknowingly married a German spy who betrayed her Resistance

colleagues.

Jacqueline, who

retained her family title of Princess de Broglie, had her head shaved

publicly as a punishment. A once-proud family, one of the richest in

Europe, was humbled.

As old age set in,

Daisy’s thoughts returned to her childhood. Her mother had

committed suicide when Daisy was only four. Now her thoughts moved

along similar lines and on more than one occasion she attempted to

take her own life.

The long-suffering,

fun-loving Reggie, who she stuck with till the bitter end, died

around the time of her 63rd birthday. Daisy returned to Paris, to a

vast town-house in the Rue de Lille, and slowly the shades were drawn

around her.

She died aged 72,

but already the world had moved on. In the age of The Beatles, nobody

cared to hear about a woman who wore a shoe for a hat, had a shade of

pink named for her, collected the biggest set of priceless jewels

ever known and encouraged people to take cocaine with their cup of

tea. The new world seemed more interesting than that.