My greatest contribution as an interior designer has been to show people how to use bold color mixtures, how to use patterned carpets, how to light rooms, and how to mix old with new.

— David Hicks in "David Hicks on Living—with

Taste" (1968)

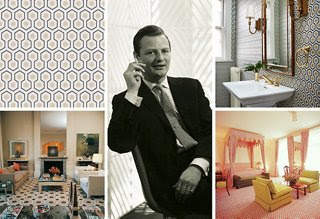

David Nightingale Hicks was born at Coggeshall, Essex, the

son of stockbroker Herbert Hicks and Iris Elsie (née Platten). He attended

Charterhouse School and graduated from the Central School of Arts and Crafts.

After a brief period of National Service in the British

army, Hicks began work drawing cereal boxes for J. Walter Thompson, the

advertising agency. His career as designer-decorator was launched to

media-acclaim in 1954 when the British magazine House & Garden featured the

London house he decorated (at 22 South Eaton Place) for his mother and himself.

An early introduction by Fiona Lonsdale, wife of banker

Norman Lonsdale, to Peter Evans initiated business partnership in London as the

pair, now joined by architect Patrick Garnett, set about designing, building

and decorating a restaurant chain (Peter Evans Eating Houses) in London's

"hotspots", such as Chelsea and Soho.

Evans said of Hicks:

"[He] was without a doubt a genius. He would walk into

the most shambolic of spaces that I had decided would be a restaurant, a pub or

a nightclub and, lighting up a cigarette, would be out of the place within ten

minutes, having decided what atmosphere it would generate because of what it

would look like. He always got it spot on.”

Hicks and the architectural practice Garnett Cloughley

Blakemore (GCB) collaborated on a series of private commissions, including a

house on Park Lane for Lord and Lady Londonderry and an apartment for Hicks's

brother-in-law, film producer Lord Brabourne. The firm also worked on a new

house in London for Hicks's father-in-law, Earl Mountbatten. GBC achieved

international recognition when it refurbished the George V Hotel in Paris for

the Trust House Forte group. Stanley Kubrick's 1971 film A Clockwork Orange

featured GCB's Chelsea Drugstore.

Hicks's early clients mixed aristocracy, media and fashion.

He did projects for Vidal Sassoon, Helena Rubinstein, Violet Manners (who

became the Duchess of Rutland), Mrs. Condé Nast and Mrs. Douglas Fairbanks,

Jr.[2] He made carpets for Windsor Castle and decorated the Prince of Wales's

first apartment at Buckingham Palace. Hicks started to design patterned carpets

and fabrics when he found none on the market that he considered good enough.

These and his hyper-dynamic colour sense formed the basis of a style which was

much admired and copied. In 1967, Hicks began working in the USA, designing

apartments in Manhattan for an international clientele, and at the same time

promoting his carpet and fabric collections. Hicks also designed sets for

Richard Lester's 1968 movie Petulia, starring Julie Christie.

In the 1970s/80s Hicks shops opened in fifteen countries

around the world. He designed, for example, guestrooms at the Okura Hotel in

Tokyo, the public rooms of the British Ambassador's Residence in Tokyo, with

only mixed success, and the yacht of the King of Saudi Arabia. Hicks was a

talented photographer, painter and sculptor and produced fashion and jewelry

collections. He designed the interior of a BMW and scarlet-heeled men's evening

shoes.

He wrote, in one of his nine practical design books, David

Hicks on Living — With Taste,[10] that his "greatest contribution... has

been to show people how to use bold color (sic) mixtures, how to use patterned

carpets, how to light rooms and how to mix old with new."

Some of Hicks's later work may be seen at Belle Isle,

Fermanagh, where the Duke of Abercorn hired him to redecorate the interior of

the castle in the 1990s. Hicks decorated the duke's main house, Baronscourt, in

the 1970s.

Obituary: David Hicks

Nicholas Haslam

Thursday 2 April 1998 00:02

The Independent

DAVID HICKS was perhaps the "Dyvid Byley" of

interior designers: the only exponent of that profession the man in the street

might be able to put a name to. For nearly 40 years Hicks has been a household

word - to many a household god - and his style a touchstone of good, mad, but

never indifferent, taste.

His many books - the first, David Hicks on Decoration,

published in 1966 - have been inexhaustible quarries of ideas and inspiration

to the following generations of designers. His later work, with its massive

overscaling and deceptive simplicity greatly influenced by his hero Sir John

Soane - with frequent chapeaux to Vanbrugh and Hawksmoor - became the classical

trademark by which he will be best remembered, but it was his early decors, so

violently heathen to the cretonned hearths of post-Festival Britain that

brought him instant recognition, a well-observed and edited transatlantic-

stroke-French chic that propelled him up ladders so fast his "international

fun-folk bobble shoes", as his contemporary Dominic Elwes noted, hardly

touched the rungs.

That, and of course, his looks. Son of a distinguished but

decidedly elderly Essex stockbroker - that his grandfather lived in the reign

of George III enormously endeared David to his future father-in-law, that

monarch's great-great-great-grandson Earl Mountbatten of Burma - and an

intelligent and sensitive mother whose culinary skills were to be a boon to

David's early bachelor life, he was born in 1929 and christened David

Nightingale - perhaps the closest he ever came to natural modesty: he was

probably correct in claiming that he alone had invented the profession of

interior designer - as opposed to mere decorator.

He was educated at an unloved Charterhouse, followed by a

hated but then obligatory stint in the Army ("smelly young men my own

age") which determined him to be his own master, and he enrolled in the

Central School of Art and Design in London. This led to contact with

advertising agencies and photographers such as Terence Donovan, for whom he

would frequently "and brilliantly" decorate sets.

At the same time he acquired the first of what was to be a

series of ravishing country houses, the Temple at Stoke-by-Nayland in Essex,

which he had often bicycled past as a child. Here he created his first decors,

devised his first garden (the long dark canal before the Temple's facade would

feature frequently in his own and clients' landscapes), gave his first parties,

invited his first friends - one of whom remembers, "I'd put a slice of

lemon in the gin and tonic. David was aghast. 'What do you think this is? A

restaurant?' " Other friends were mainly of the more sophisticated world,

headed by Bunny Roger, Arthur Jeffress, Barry Sainsbury and those veteran,

inveterate matchmakers Chips Channon and Peter Coats.

In Hicks's incandescent glamour and vaunting talent, they

saw vast potential. Some dazzling union must be achieved: a marriage of

patrician wealth and raw ambition. It was. In 1958, joined by the equally

brilliant young decorator Tom Parr (who went on to head Colefax and Fowler),

Hicks and Parr opened in London on Lowndes Place, off Belgrave Square. No one

who was there that first evening will forget the 27 metal African lances hung

exactly five-and-a-half inches apart, horizontally, on one wall, or a thousand

watts lighting, in relief, a vast baroque torso. The spare sparse energy, the

space, the scale, were literally breathtaking. The David Hicks style had truly

arrived.

So much so, indeed, that he moved into 22 South Eaton Place,

where he and his mother would entertain - David's fantasies, her food. The

decor became the cynosure of eyes. Carpets and curtains were banished. Books

must be bound all white. Monotones prevailed - as Vere French confessed,

"When Hicks and Parr said beige, who was I to lag behind?" The

ultra-modern art hung frameless, the white flowers in lit glass tanks. Baths

and beds bestrode the middle of rooms, David's pugs could only eat off Chinese

blue and white. It was all very surprising.

But David Hicks could always surprise. In 1960, the

announcement of his grand marriage to Lady Pamela Mountbatten amazed all but a

very few. "Oh I don't call that grand," his friend Tony

Armstrong-Jones remarked. (Five months and a title later revealed why.)

Henceforward Hicks's clients and life style took an acutely

upward turn, the former providing the latter - a couple of beautiful

18th-century houses, one in St Leonard's Terrace in Chelsea, the other the

near-stately Britwell in Oxfordshire, which his wife ran with exquisite grace

and tact. Hicks joined the squirearchy, rode, learnt to shoot (extremely well)

and allowed his never-over-repressed ego to blossom ("I'm very famous and

clever and I'm married to a very rich lady") as well as

bourgeoisie-teasing pronouncements: "Red and yellow dogs are fearfully

common" (red was later applied to cattle with equal rigidity),

"Daffodils are hideous"; and I remember a postcard from "the

Rainforests. Another of God's mistakes" - an almost Firbankian comment.

Concurrently his fame and influence spread world-wide, his

influence and hauteur making him a kind of interior dictator. One besotted

client on the Iberian peninsula kept Hicks's room "as he left it" and

would allow friends to glimpse the grail through a barely opened door. But

clients became friends, always - Hicks's immense knowledge, enthusiasm and

humour saw to that. He frequently invited Elaine Sassoon, who, when married to

Vidal, had been among the first, and the intensely private Nico Londonderry

Fame was a lifelong confidante. His talent for friendships echoed his

temperament. His standards were high, he hated many things and people, but once

in his pantheon he would never ever let them down. Hicks was too worldly to be

cruel.

He was let down, himself, however, by a disastrous business

liaison which wreaked unaccustomed havoc. Hicks, with his reserve of courage

and that irrepressible ego, retrenched and reorganised, building and decorating

in many countries, but concentrating now on garden design, at which he was

perhaps even more talented and original. The best example of his new- found

genius is his own garden at the Grove, the lovely house in a fold of the valley

below Britwell, where Pamela and he lived their elegant, harmonious,

rock-and-royalty life for the past 20 years.

Here he could indulge in forcing nature into the linear and

geometric patterns he so loved to use indoors, and devise elaborate humours - a

trompe church steeple was attached to a hay-cart so that he could instantly

terminate a distant view. And it was here, his handsome family around him, that

David Hicks left, in tranquillity, the life he had so exuberantly adorned.

David Nightingale Hicks, interior decorator and garden

designer: born Coggeshall, Essex 25 March 1929; director, David Hicks Ltd

1960-98; married 1960 Lady Pamela Mountbatten (one son, two daughters); died

Britwell Salome, Oxfordshire 29 March 1998.

Taste is not something you are born with, nor is it anything

to do with your social background. It is worth remembering that practically

anyone of significance in the world of the arts, whether in the past or today,

was nobody to start with. Nobody has ever heard of Handel's or Gainsborough's

father.

My passion for arranging masses of things together is part

of the way I see objects and use them. It not only looks mean, but is visually

meaningless, to have one bottle of gin, one of whisky, a couple of tonic water

and a soda syphon on a table in the living-room, even though that might be

perfectly adequate for the needs of one evening's entertainment.

It is perhaps I who have made tablescapes - objects arranged

as landscapes on a horizontal surface - into an art form; indeed, I invented

the word . . . What is important is not how valuable or inexpensive your

objects are, but the care and feeling with which you arrange them. I once

bought six inexpensive tin mugs in Ireland and arranged them on a chimneypiece

to create an interesting effect in a room which otherwise lacked objects. They

stood there in simple perfection.

I dislike brightly coloured front doors - they are more

stylish painted white, black or other dark colours. I hate wrought iron. I

loathe colour used on modern buildings - it should be inside. I do not like

conventional standard lamps - I prefer functional floor-standing reading

lights. Function is just as important as aesthetics . . . Function dictates

design.

From David Hicks, Living with Design, Weidenfeld &

Nicolson 1979

No comments:

Post a Comment